The Fiction index!

When Mikhaíl Nikolaievich Arkhipov first arrived at Chelyabinsk, it was with a certain nausea brewing in his stomach. The town was a tiny nothingness in the dark of Near Siberia, a few poorly defined dirt tracks that crossed one another in front of the rotting shell of Chelya Fortress. He'd been forced to get off the train half a hundred versts back, for that was the nearest station. From there he'd hired a coach, which followed the road of crushed gravel as far as it could, then dove over farms and countryside towards Chelyabinsk. Mikhaíl's presence in the town was something of a prodigy. The imperial government didn't care much about Chelya these days. The threats of banditry were over, and there hadn't been rumors of rebellion in fifty years. Those dark nights had belonged to the distant past, to a generation now too old to care if the hand of Imperial Russia spread out over their land, too crooked and riddled with ague, pox, and time itself to raise their guns in rebellion against the Tsar. There was no reason for officials to come to Chelyabinsk, then, at all. Except Mikhaíl had come. Autocrat Nicholas, Emperor of Russia, left nothing to chance. His brother Aleksandr had been implacable as Tsar; Chelyabinsk had, for a brief time, been a circus of activity as those imprisoned in the failed Decembrist Revolt were shipped ever northward into the wilds of Siberia.

Nikolaievich felt as though he must void his stomach into the snow. This filthy lane of hovels and its attendant versts of snow-covered farms were to be his commission, the reward for his years of service to the imperial government. The fortress which he was sent to command was a decrepit ruin. There were no signs of any soldiers within—no lights, no fires burning, and none of the easy camaraderie of men stationed in the back of beyond. He had hoped to find coffee at least, but none of the serfs in the town were likely to have it. It was a luxury that only city-dwellers and soldiers were like to have, and there seemed to be no soldiers here. Before he stepped from the hack, he opened the large logbook he had been provided. Yes, there were fifty names there where he thought they should be. Yet there was no possible way the fortress contained fifty men. He could see from here, even peering through thick veils of falling snow, that the barracks' roof was caved in and many of the walls partly pulled down. Probably the serfs had started attacking the brickwork once the place was abandoned to make it into walls for their fields.

He hauled his luggage from the coach with the help of the driver. "Where can I go to stay?" he shouted against the wind. His gut was rebelling, threatening to spill into his mouth. What had he ever done to deserve this post?

"I don't know," the driver bawled back, "I don't know this town. No one comes here!"

"I am the first," Mikhaíl said.

The driver nodded. "Yes," he confirmed, "the first. Goodbye."

So there he was, alone in the snow, with his cases like standing stones all around him slowly gathering a dusting. He cursed the Tsar and the luck that had sent him here. Where would he go? Certainly not into Chelya Fortress to freeze to death in some dank cellar. The serfs would simply have to put him up. After all, he was an Imperial Officer; they couldn't very well refuse.

The first door was answered by a glowering woodsman the size of a horse. His brow beetled at seeing Mikhaíl's uniform, and his lip curled back in something like a sneer when his eyes alighted on the pistol and sabre in his belt. "I must find the Intendant of Chelya Fortress," Mikhaíl said. "And suitable lodgings for the night."

"The Intendant," the ogre repeated back to him. His beard alone could have covered an ox with ease. He said no more and the two men stared at each other. Mikhaíl felt the stirring of anger in his breast, comingled with fear. He wasn't going to be cowed by an idiotic peasant on his first assignment, no matter how huge the man was.

He gripped the hilt of his sabre firmly and threw back his shoulders. "If you cannot tell me where he is, I demand you step aside at once and offer me the shelter of your home—as is your duty."

"My duty," said the man. Perhaps he was slow, Mikhaíl thought. Perhaps he had been kicked in the head by an ass. "My duty to whom?"

This beggared belief. Mikhaíl put as much fire into his gaze as he could, pushed forward so he was nose-to-chest with the giant. "Your duty to the Tsar of Russia, you swine! Now stand aside and let me in or I shall be forced to thrash you. I have a flogging whip in my effects. Do you wish to see its use?" He snarled.

The titan shrugged. "If you say so," he said, and then turned to bellow into the house. "OKSANA! We have a guest by order of the Tsar! Prepare him a bed and some food. You would like some food? Good."

He was lead into the filthy domicile of this churlish behemoth and suddenly hugged tight by the warmth that permeated the house. There was a fire blazing in the hearth, throwing shadows every which way. The interior of the house seemed ghastly bright, more so even than coming in from the dark could account for. It took a moment for Mikhaíl to realize what he was seeing: light reflected in crazy patterns off three huge silvered mirrors hanging on the far wall. He frowned. Where had peasants gotten such things? But he hardly had time to consider it before the giant guided him to a table where he was served a simple peasant fare for his dinner.

As he ate, he began to realize that there were other oddities about the house as well. There seemed to be, upon every shelf and surface, little brick-a-brack. Small trinkets that were nothing in and of themselves, but upon examination and close study turned out to be... buttons. Brass buttons. And there a buckle. Oh, and over there what was unmistakably a powder horn. He had the dark suspicion, suddenly, seize him that the soldiers who were meant to be garrisoning the fort had abandoned their posts and now lived as farm-folk amongst the peasants. Discovering their secret would surely be grounds for murder—who would know that the poor stupid Intendant Nikolaievich had disappeared? It would take six months or more for Moscow to begin to wonder, and by then he would lie in some deeply dug grave in the wilderness. No one would even be able to find his body. Such was Siberia! So he kept his mouth shut and his suspicions to himself.

He was given the loft to sleep in, the giant and his crabbed little woman taking up by the fire. He had a blanket, and a mound of hay to sleep upon, and that was good enough for now. His suitcases were downstairs by the door, but he kept his pistol primed and nearby and his sword hugged tight to his chest. He drifted off with the hot burn of serf's vodka spreading a pleasant warmth through his stomach, his arms, his head. He just had time enough to think that they probably hadn't paid the proper vodka excise on their alcohol before he drifted off.

When he woke, it was to a strangely disorienting sight. He had no idea where he was for a moment, and terror thrummed in his every limb. He remembered in a rush and soon he was able to match the fantastic angles and dim corners of the now-darkened house with the brilliant room he had entered earlier that night. The fire had burned down to evil looking embers, glowing with a faint throb of ruddy life. He leaned over the edge of the loft to find that his hosts were nowhere to be seen. His own face leered back at him from the mirror hanging in the center of the wall and he pulled back.

It was then that he heard the voices, which must have been the cause of his waking. They were whispering: a man and a woman. Too faint to make out what they were saying, the sound of their exhalations was like the long nails of feeble old man too ancient to cut them scrabbling on wood. He pressed his ear against the boards beneath him, but only managed to dampen the sound. He cast around him and saw a small gap in the floor by his feet through which a tiny gleaming eye of red light could be seen. He carefully crawled to it, attentive to make no sounds lest he rouse his hosts to his own presence.

"We will do what we have always done," Oksana was saying. "We will let it be handled by the others."

He heard the giant huff. "I am tired, woman. Tired of all this pretending. Why do we not tell him at once, and let him make his own decision? If someone had given me the choice—"

"Then what? You would have drowned yourself? You lack the courage."

"The soldiers, the soldiers had swords and guns. I could have shot myself, back then. That would have been a mercy. Now there is—" he stopped. There was a noise, a faint slithering sound, from the area of the room near the hearth. Mikhaíl pressed his eye to the hole to see crooked little Oksana shy away from her giant of a husband and the huge man staring grim-faced. The slithering came again, so Mikhaíl backed from the hole and wriggled his way to the edge of the loft a second time.

What he saw arrested him completely and set his entire body in convulsive jitters, small involuntary movements that made no sound, but still clasped and unclasped his muscles in a horror show of tension. His skin was covered with silvery sweat, ice cold as it poured from him. For he saw the surface of the center mirror begin to shift and move of its own accord. There were, reflected in it, three men and two women, all staring into the room with hideous intensity. Their eyes seemed like they could bore through wood, stone, soft and malleable flesh. What peasant sorcery was this? For though they stood reflected in the room, the room was empty.

The worst sight, the most horrible, was the image of his own reflection. For though he was looking at the mirror, the reflection of his own face was looking back at him. It had the same terrified expression, but it was staring soulfully into him. Then, as he watched, his face frozen in terror, he saw a hideous smile come over the face in the mirror, and it winked at him. He screamed and fell from the loft into a tumble below.

A second waking. He was cold, though the room was well-lit by the fire. He was surrounded by soldiers in their uniforms, all murmuring quietly to each other. He shot up. "Where is the mirror? Where are those serfs?"

"Intendant," said a man with a fine mustache and a well-trimmed beard. "Please, don't be agitated. It won't help anything."

"Won't help?" he asked. "Won't help?" He got to his feet. "Why the hell is it so cold?" The men exchanged bleak glances. "What is it, you damn deserters?"

"Deserters!" exclaimed the man who'd spoken. He wore little spectacles as well, Mikhaíl saw. "No, no, no, you misunderstand. We cannot desert. We can't go anywhere, Intendant."

"Well, answer me this: where did those peasants get their cursed mirror from? It's got some kind of damned power!" Another look between the men.

"They took it from Chelya, sir. We had several of them. You see, one day some of the men started acting... strange. I couldn't determine what had caused the lapse. They failed to show up for drills and then their comrades began to speak of unsettling changes that had come over them. Changes that had no explanation. They began to prefer different foods. They seemed not to know the details of intimate relationships they had, only days before, been having with peasant girls. They were... just... different."

"Bohze moi," Mikhaíl breathed, "You're Intendant Dmitrievich."

The man nodded. "I'm sorry you were sent to find out what happened to me."

"I was?"

Dmitrievich looked uncertain for the first time since Mikhaíl had awoken. "I thought so. Doesn't the capital wonder where we are... what we're doing? Why we've made no formal reports?"

"But you have," Mikhaíl argued. "Just last week in Moscow you—"

He blinked. Behind Dmitrievich he saw the mirrors on the peasant's wall. It was reflecting the room well enough, but none of the soldiers were in it. In the reflection, he was sitting at a chair and... eating. And on either side were Oksana and the giant. "What..." he murmured. Warmth, the only true warmth in the room, seemed to flow from the frame of the mirror. He pushed Dmitrievich aside and walked towards it. His hands outspread, he placed them on the glass, which felt like living flesh. From the other room, the room in the mirror, he saw himself turn to look. He gazed into his own eyes and knew, with vomitous horror, that the thing looking back was not him.

Friday, February 28, 2014

Thursday, February 27, 2014

A Note on Roads and Cities

Roadways and tracks swell around cities, they proliferate and spread like a thousand veins feeding lifeblood into its gates. Lots of fantasy presents cities as this sort of isolated environment, springing mushroom-like from the plain. The existence of subsidiary towns and tributary villages that surround cities in a network of roads and lanes is a well known and well studied effect; this area is often called the cities' hinterland and is even recognized in medieval law sources as a verity. Communes, that is cities that have been granted special charters making them semi-autonomous rather than the private holdings of an individual nobleman, generally include within their jurisdiction a belt of towns a few miles wide in every direction. These towns feed the city, they bolster its industry, and they provide it with all kinds of goods not available in an urban environment. I can't think of the book off the top of my head, but there's a great economic history of the middle ages that has a series of interesting hexes and algorithms used to predict (and describe) the size and distribution of towns and villages, middling sized cities, and large cities. This system uses as its basis the idea of "breaking and bulking," an economic feature of market centers.

When you stand outside the walls of a medieval city, you are standing on a track that runs all around them, from gate to gate. Sometimes the gate you want to enter is closed or busy or has a tariff on it. This means you'll travel to another one of the many gates, and enough people do this over time that even were it not part of the design feature of the city, this track would be created by the simple action over time of merchants with caravans attempting to find the optimal entry-point.

Spreading out from this ring-shaped track are farms and pasturage, intertwined by tracks and roads that link them together and to the city from which they receive their rights. Much like a fortress, these are the places that will be raided and burned if the city invokes the ire of an enemy or the extension of royal policy calls for war on that particular commune (the War of the Lombard League comes to mind). Beyond these will be found a number of satellite villages that serve the city in much the same way and may be subject to the same types of reprisals by invading armies.

Furthermore, cities grow up on trade routes where major roads cross (or trade crosses from roadway to riverine, or oceanic, or riverine to oceanic, or however it may be). It is rare indeed for a city to be located 'nowhere,' ie, not on the conflux of other trade lines. The algorithm for computing city locations must always be manually bent to take into account the location of the major trade routes—big cities serve as anchor points, and the small villages and medium market towns spread out like pockmarks from this central location, naturally springing up.

To overcome this economic certainty would require major intervention by fantasy factors. The existence of widespread flying trade on the backs of carpets or pegasi, for instance, might justify the presence of a city in a remote mountainside or a historical factor such as the removal of an entire people to a protected mountain-fastness (Machu Picchu, for instance) would provide a less fantastic reasoning. Still, understanding the basic distribution of cities and markets is important so that when you break that reasoning, at least you know why.

When you stand outside the walls of a medieval city, you are standing on a track that runs all around them, from gate to gate. Sometimes the gate you want to enter is closed or busy or has a tariff on it. This means you'll travel to another one of the many gates, and enough people do this over time that even were it not part of the design feature of the city, this track would be created by the simple action over time of merchants with caravans attempting to find the optimal entry-point.

Spreading out from this ring-shaped track are farms and pasturage, intertwined by tracks and roads that link them together and to the city from which they receive their rights. Much like a fortress, these are the places that will be raided and burned if the city invokes the ire of an enemy or the extension of royal policy calls for war on that particular commune (the War of the Lombard League comes to mind). Beyond these will be found a number of satellite villages that serve the city in much the same way and may be subject to the same types of reprisals by invading armies.

Furthermore, cities grow up on trade routes where major roads cross (or trade crosses from roadway to riverine, or oceanic, or riverine to oceanic, or however it may be). It is rare indeed for a city to be located 'nowhere,' ie, not on the conflux of other trade lines. The algorithm for computing city locations must always be manually bent to take into account the location of the major trade routes—big cities serve as anchor points, and the small villages and medium market towns spread out like pockmarks from this central location, naturally springing up.

To overcome this economic certainty would require major intervention by fantasy factors. The existence of widespread flying trade on the backs of carpets or pegasi, for instance, might justify the presence of a city in a remote mountainside or a historical factor such as the removal of an entire people to a protected mountain-fastness (Machu Picchu, for instance) would provide a less fantastic reasoning. Still, understanding the basic distribution of cities and markets is important so that when you break that reasoning, at least you know why.

Wednesday, February 26, 2014

Gonzo Gaming and the OSR

The OSR is carried upon a strong current of gonzo play—outlandish charts, insane ideas given flesh, and hallucinatory episodes that produce games which feel like Jodorowsky's Dune. I have no problem with this, I love this idea—but my mainstay in gaming in something a little more concrete. This is an understatement of hyperbolic levels, since I tend to map out every inch of land and record the most minute details of political systems whereas the Gonzo Gaming mantra is generally to make something up on the spot and if you're stuck consult a table full of wholly insane options to help you.

That being said, I don't generally gravitate to that type of gaming. The last gonzo setting I designed/thought of running was Zaan (specifically engineered to resemble something that a 14 year old kid might draw in the margin of his notebooks) and the last one I thought of playing in was the fabulously insane Planet Motherfucker. NORMALLY, however, I have a laserlike focus on detail and require my material to provide me with hundreds of pieces of information, nay thousands, that most people don't fixate on.

Somehow, gonzo gaming seems to be much more liberating, or at least it does right now. I've been working on the 10th Age off and on with three or four months here and there in between intense development sessions, for around FIVE YEARS. I love the detailed, fussy thing that has resulted, the vast alternate otherworld of medieval (and early medieval at that) influences. But sometimes I get tired from running something that requires an attention to detail usually reserved for insane librarians and archivists. I look out into the vast web and see things like the beautifully worded Hill Cantons and wonder why I can't spew that sort of inspired insanity in my games.

That being said, I don't generally gravitate to that type of gaming. The last gonzo setting I designed/thought of running was Zaan (specifically engineered to resemble something that a 14 year old kid might draw in the margin of his notebooks) and the last one I thought of playing in was the fabulously insane Planet Motherfucker. NORMALLY, however, I have a laserlike focus on detail and require my material to provide me with hundreds of pieces of information, nay thousands, that most people don't fixate on.

Somehow, gonzo gaming seems to be much more liberating, or at least it does right now. I've been working on the 10th Age off and on with three or four months here and there in between intense development sessions, for around FIVE YEARS. I love the detailed, fussy thing that has resulted, the vast alternate otherworld of medieval (and early medieval at that) influences. But sometimes I get tired from running something that requires an attention to detail usually reserved for insane librarians and archivists. I look out into the vast web and see things like the beautifully worded Hill Cantons and wonder why I can't spew that sort of inspired insanity in my games.

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

7th Sea: A Tactical Study of El Morro

or: Why is that fortress so damn important?

This is something I've mused over for many hours. The 7th Sea books can be amazingly detailed and they can also be hopelessly vague. The question here is this one: With two hundred miles of Rio del Delia, why is Montaigne so focused on capturing El Morro, and why does it serve as the lynchpin of the western Aldana defense? As presented, there are no answers. All it takes is a few moments looking at the map of Théah to realize the Montaigne should just go around the great fortress and either cut its causeways from behind, or simply bypass it and stretch their supply lines to capture San Cristobal where they would be able to, at once, begin reinforcing their army by sea and thus take Vaticine City without worrying about the forces at the Black Fortress.

Here, then, are a number of reasons why El Morro is the most important fortress in Castille and the Montaigne may not easily abandon its investment:

1) Attempting to cross El Rio del Delia would leave San Tropal exposed. The city of San Tropal, at least the way I have set things up, lies about a quarter or half mile from El Morro. If the Montaigne forces left in Castille (which are less than robust after the withdrawal of Montegu) were to attempt to forge another crossing, the garrison at El Morro would easily overrun San Tropal and its guardian fortress, thus pushing back the Montaigne conquest. Since a Castillian army in Torres would inspire insurrection and untold sorrows, the Montaigne cannot afford to take this risk.

2) The process of fording del Delia would take too long. By the time the Montaigne Armée Soleil had arrived at the location they were going to make the crossing and prepared to cross in force, a Castillian army would be ready to meet them. Well-supplied from its unbroken line to El Morro, this army would hold defensive territory while the Montaigne attempted to fight over a river, possibly in small rowing boats, large barges, or upon a hastily constructed pontoon bridge.

3) As long as El Morro stands, the river is in Castillian hands. Though Montaigne sea-power might be mighty, they have no riverine vessels capable of contesting the Castillian navy that regularly sails up the Delia. They cannot bring their navy to bear along the rivers due to their prohibitive width, thus meaning that whoever controls the most powerful fortress along del Delia's banks may also move ships with impunity. These Castillian naval vessels could easily sever contact from an army that crossed to the far side or, worse, destroy the army while it was crossing.

4) The garrison of El Morro can speedily redeploy. This is related to numbers 1 and 2 but is more applicable as a general rule. Once the investiture of El Morro ceases, its defenders are free to reposition anywhere they want to face the Montaigne army. As long as San Tropal continues making at least a showing of assaulting the fortress, they are trapped where they are.

This is something I've mused over for many hours. The 7th Sea books can be amazingly detailed and they can also be hopelessly vague. The question here is this one: With two hundred miles of Rio del Delia, why is Montaigne so focused on capturing El Morro, and why does it serve as the lynchpin of the western Aldana defense? As presented, there are no answers. All it takes is a few moments looking at the map of Théah to realize the Montaigne should just go around the great fortress and either cut its causeways from behind, or simply bypass it and stretch their supply lines to capture San Cristobal where they would be able to, at once, begin reinforcing their army by sea and thus take Vaticine City without worrying about the forces at the Black Fortress.

Here, then, are a number of reasons why El Morro is the most important fortress in Castille and the Montaigne may not easily abandon its investment:

1) Attempting to cross El Rio del Delia would leave San Tropal exposed. The city of San Tropal, at least the way I have set things up, lies about a quarter or half mile from El Morro. If the Montaigne forces left in Castille (which are less than robust after the withdrawal of Montegu) were to attempt to forge another crossing, the garrison at El Morro would easily overrun San Tropal and its guardian fortress, thus pushing back the Montaigne conquest. Since a Castillian army in Torres would inspire insurrection and untold sorrows, the Montaigne cannot afford to take this risk.

2) The process of fording del Delia would take too long. By the time the Montaigne Armée Soleil had arrived at the location they were going to make the crossing and prepared to cross in force, a Castillian army would be ready to meet them. Well-supplied from its unbroken line to El Morro, this army would hold defensive territory while the Montaigne attempted to fight over a river, possibly in small rowing boats, large barges, or upon a hastily constructed pontoon bridge.

3) As long as El Morro stands, the river is in Castillian hands. Though Montaigne sea-power might be mighty, they have no riverine vessels capable of contesting the Castillian navy that regularly sails up the Delia. They cannot bring their navy to bear along the rivers due to their prohibitive width, thus meaning that whoever controls the most powerful fortress along del Delia's banks may also move ships with impunity. These Castillian naval vessels could easily sever contact from an army that crossed to the far side or, worse, destroy the army while it was crossing.

4) The garrison of El Morro can speedily redeploy. This is related to numbers 1 and 2 but is more applicable as a general rule. Once the investiture of El Morro ceases, its defenders are free to reposition anywhere they want to face the Montaigne army. As long as San Tropal continues making at least a showing of assaulting the fortress, they are trapped where they are.

Monday, February 24, 2014

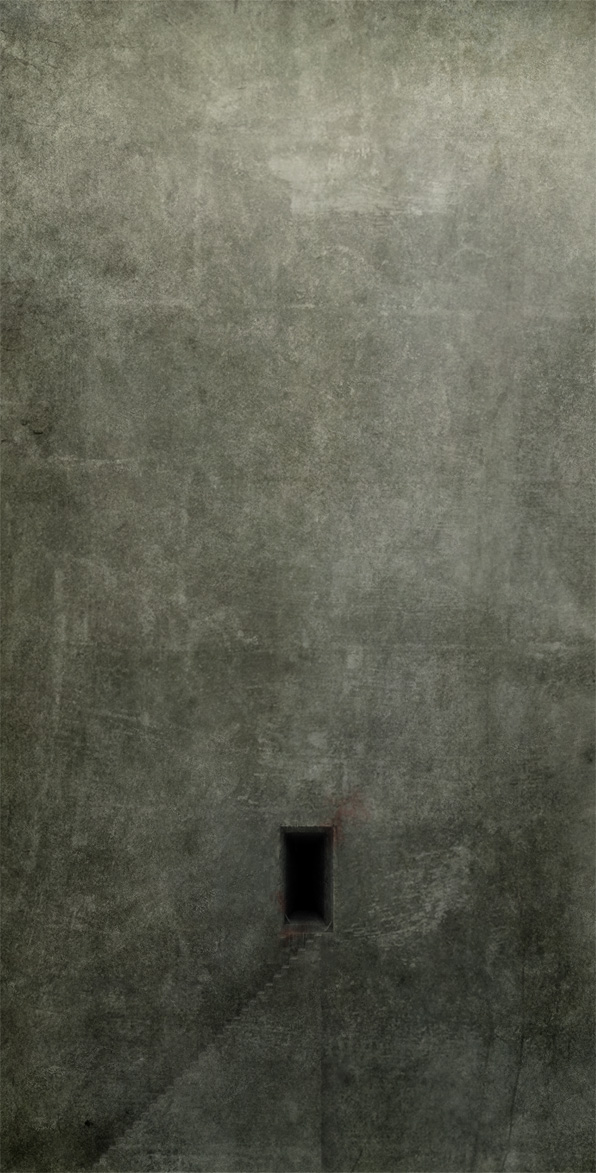

Horror Vacui

|

They say the universe abhors a vacuum. In truth it is mankind that abhors the vacuum, mankind that cannot look into the emptiness and not be shaken. Staring into nothingness reminds us of our own emptiness, reminds us of the not-so-secret truth hiding beneath the congerie of complexity that decorates every surface. We surround ourselves with calcifications, the encrustation of centuries to convince ourselves that the screaming wild, the howling void is not lurking behind every façade.

Use the Table of Dark Truths however you desire; perhaps when a wizard goes mad from magic exposure, or when you're designing your setting, or just to add something awful to an already-designed one.

Table of Dark Truths

1. The gods are dead. Whatever magic is enacted through priests comes form a far different source, though the secret may never be known. Drawing power from these upsetting and evil places strengthens them. Worship sent to the nonexistent gods only makes the slimy crawling things at the base of the universe stronger.

2. Men and goblins are united in one horrific circle. The wretched beast called man is the host of a vicious and endemic parasite which can only bloom within the bodies of goblins. Thus, the two races are intrinsically linked at a vile and biological level; the parasite drives men to find and be slain by goblins, and is the root cause of all adventure. As the parasite matures it encourages more and more reckless behavior until the host is slain, hopefully in a dungeon. Exposure to the damp dungeon atmosphere encourages parasite growth.

3. Elves feast upon the flesh of man and dwarf. This dark secret is one of the keys to their immortality. They never let anyone outside their realms know of this secret if they can help it, but the hunger is necessary; whether by dark curse or black magic. Elves, of course, were once goblins or men but elevated themselves above their station in ancient time-before-time with this hideous trick.

4. The womb of the earth is nightmare. Far from being the source of fecundity that most farmers think of, crops are grown by the sun and rain. The earth births horrors; the buried dead feed it, and from their tombs there grow monstrous spirits of all kinds that are released through the soil as gaseous vapours into the night. Treading in a graveyard past sundown is foolhardy at best, as the beloved mother earth is a corpse which grows only cancers.

5. Magic rots the body of the magician. This secret is one kept by all powerful wizards. They perfume themselves with pomanders and incenses, dress their horrific bodies with sweet-smelling linens, and slowly creep towards lich-hood. Those who survive the hideous process assuredly never tell their apprentices that they shall one day become walking corpses, animated only by their own deathless will. Every level of wizard or magic user achieved beyond 9 causes the wizard to lose 1 point of charisma as the rot spreads; if their charisma ever reaches 0 for any reason they die, though magic may mitigate this and those who die in this fashion may return as NPC liches.

6. This has always been your fate. The world is a hollow sham, manipulated by dark forces behind the shadows. The choices you thought were your own were someone else's. You cannot avoid the fate in store for you, for every deception you think you uncloak is merely a mask for another layer of deceptions. This malignancy goes down unto the very root of the world and behind the smiling faces you think of as your friends lurk unhuman things that know more about you than you do yourself.

7. The world is peopled with whispers. The nightwhispers, they are called, and they can only be heard in certain secret and lonesome spots where the sounds of nature and man both fade to naught. Squatting on the dark of night in a place where there is no sound whatsoever save your own breathing will allow you, after a time of fervent concentration, to listen in on the whispers. The longer you listen, the more you focus and strain, the louder the whispers will become. It is said that the first magicians were men who listened overlong to the unintelligable ramblings of the night. Listening to the whispers for more than an hour requires a system shock check or the listener goes mad. If they succeed, they may immediately make a learn spell check to learn one spell of any level that they have access to OR, if thye are not a wizard or magic user, a spell of level 1d8 which they can prepare once a week as a wizard of the minimum required level.

8. Reflections show more than they appear. Did you ever wonder why a cloned copy tries to kill its mate? It is because it burns to live, to be in a sense real. These shadow worlds that mirrors reflect are peopled with half-real phantasms that desire life. If someone dies within visible range of their own reflection, there is a 30% chance that the phantasm crosses the boundary and assumes their position, name, and station in life.

9. Something is always listening. No matter what you say, no matter where you say it, no matter who you say it to... something is listening to you. There are ways of getting in touch with this something, of finding out what others have said, or striking bargains with it for knowledge. None of these bargains ever work to your benefit in the long term.

10. All that glitters. Dwarves will kill for gold, though they don't want any other race to know the depth of their hidden depravity. Whenever a dwarf feels cheated of his due in gold, he must make a system shock check or attempt to murder the cheater. Whenever a dwarf sees a quantity of gold equal to 1,000gp x the dwarf's level, he must save vs. paralyzation or immediately attempt to acquire it through any means necessary.

11. Gnomes are not alive. Not in the traditional sense, that is, in that they are cohesive individuals. They are the eyes and ears, the hands and fingers, the protrusions of a cosmic thing more ancient than elves or dwarves or mankind that has inscrutable purposes in the world. Any PC gnome that dies may immediately roll up a new gnome that has half the experience of the dead character and seems to inexplicably know things that the dead gnome knew.

12. Horror Vacui. The mind may never be at rest, lest it ingest itself. It cannot comprehend how bleak and awful the universe truly is. Any PC who is idle for more than an hour without amusements and things to do and has an intelligence of 13 or greater is at risk for this madness. Waiting in dark dungeon rooms without dicing or chatting is one way that this horror can sneak in. Those who have a wisdom of 15 or better are double susceptible. There is a 25% chance each hour (non cumulative) with an additional 25% chance for those of 15+ wisdom, to develop an insanity either at the DMs choice or by rolling on this chart—the roll may or may not, at the DM's discretion, indicate something that is true.

Friday, February 21, 2014

Fiction Friday: Le Sergent

Other tales at the Fiction of Yesteryear index!

Hubert was in bad want of a musket. The nearest was eight yards away, where Gautier had been shot clean through the forehead, but it had fallen on the lip of the sunken road and was in plain sight to Spanish fire. "Conneries!" he swore at himself, at the world, at the Spanish, at his men. Lieutenant Seneville was moaning like a stuck pig with a ball in his arm and another one in his leg. His hat had fallen into the mud a mere handspan from Hubert; maybe he could grab it, fling it up, and then dive for the musket. Better, though, if he could just push Seneville into the woods and use him as a bargaining tool. Would the Spanish care to take a lieutenant captive in exchange for the lives of the other partisans? Well, he'd never get the chance to find out. The asses in charge of the column, most likely the colonel himself, had issued all sergeants with huge unwieldy partisans. What was he to do if he got corps-a-corps with a Spaniard? Knife him in the eye, perhaps, while all his men had the luxury of sabres and shot.

Just as he began to slither forward to make a grab at the weapon, the Spanish poured a hail of lead into the thicket. Bushes swayed madly back and forth and tree limbs whined with shot. The puffs of musket smoke rose in a thick choking cloud above the Spanish position. Hubert had had enough. "That's it, boys!" he growled, rising to his full and impressive height. His culottes were stained with the lieutenant's blood, but his men had no way of knowing that. To them he was like some kind of avenging colossus, bloody and proud. "Charge!" he howled. Over the lip of the road they went, their legs pumping to carry their bodies to the Spanish lines before the bastardes reloaded and turned them into so much useless meat.

The Spaniards, evidently, did not think well of their chances. With huge Hubert and his men screaming war cries and ploughing through the undergrowth and their own muskets still unloaded, the foe chose instead to make a tactical withdrawal. So what if that withdrawal had the appearance of a full route, some of the rearmost being sabred to death before they even managed to scramble up out of their hiding places? Hubert, with his ridiculous partisan in hand, never got as near as a handspan to one of the enemy, but it was his action that carried the day. He grinned and told his boys, "The king don't know what he has here in you." That was their work done for the time, and Hubert could hope that they wouldn't be sent out from the column in any other foolish action for a while again. Let them rest, and the lieutenant recover, let the other boys have their turn getting shot at or chopped to pieces.

With the wood secure, Hubert made a mental count of the dead. There was Gautier, of course, and two others. He'd keep Gautier on the payroll and add his own pension to the growing pool that Hubert himself collected and kept from the pay. When were they going to get their money? Probably not until the king captured another town or a party of partisans forced some Dutch to cough up their required taxes. The creditors in Paris were waiting in a line a mile long, and each new army action sent home gold and silver from the Spanish-held Dutch as the soldiers wrung it out of the populace.

Hubert was most concerned about Seneville out of all his lot. He was a lenient commander, and as the lieutenant of the partisan detachment from the Reg. de Lyonnais he was sergeant Hubert's direct superior. He never pried into things like the number of dead men against the number still alive to draw pay or the misappropriation of goods. Hubert had a small business on the side melting down extra shot and selling the lead to the Dutch for the repair of roofs damaged in the war. Gautier had been one of his chief confederates in that operation, which was all for the good because he'd been getting a little persnickety lately. Nothing put an end to a good career in the army like getting snitched out. Oh well. Au revoir, Gautier!

They returned to the column with Seneville on a makeshift stretcher, screaming every time one of the men jogged or jostled him. That left Hubert to make his report to the adjutant, which he did before going off to have a smoke and a fuck in the train. They'd been in the Netherlands for a year and a half now, and the fighting hadn't gone as Hubert had hoped. When he'd first signed on, scrawling his name on that sheet of paper as the drummer played patriotic rhythms and the recruiter had clapped him on the back and bought him a lager, he'd imagined standing up in one or two great setpiece battles, making his fortune from looting the dead, and taking the proceeds to buy a fine farm or some other business.

What had he got? Ten thousand Spanish forts, bogging down the army every step of the way. The clap once, and crabs. The whores that followed the Armée Royale were infinitely less clean than the farm-girls in neighboring villages. But the villages were Dutch and Lebeau had been caught just last week in a rick with some straw-haired lass and had his cock chopped off by her father and three Spanish soldiers before being sent stumbling back to the column, culottes all bloody from his excised organ, to show the French what happens to men who fuck little farm girls.

That was nothing, Alberte said. He was one of the old hands in the war, telling stories from all kinds of campaigns in Europe. He seemed to shave once a fortnight, perpetually stubbly was he. He also stank from refusal to bathe—"It'll rain soon enough, or the damn Dutch will bring the sea to us." It was a kind of fervent superstition. He told stories of Dutch Republican partisans breaking up dikes to flood out army positions and drown horses. "Yer lucky we ain't seen none a' that yet. But we will." We will, we will. That was Alberte's constant promise. Lucky we haven't seen the pox spread through the army... but we will, we will. This litany, this oration, was enough to drive you mad. That was part of the reason Hubert spent so much of his time among the camp followers. The other was, of course, that he had a purse swollen with the money of dead men and not enough ways to spend it. What good would it do to be a rich man only to have your face shot out the next day? No, better to lay with as many women as he could, drink as much as he could stomach, and pass out before the battle.

It was with shock and horror, then, that Hubert awoke to the sound of men acclaiming the king. Le roi de Soleil was present in his column. He scrambled out of his sweat-sodden sheets and tried to dress. The whore was little help to him, pawing at his naked ass and back, purring to receive his custom just once more. He glared at her and thought about striking her, but the ensuing fight would make him even later. For her part, she did her level best to please him and draw him back into bed just one more time—for she had a daughter and son in a village on the border who were in need of food and roofing. If Hubert had known, he might have paid her in stolen lead. As it was, his haste left behind a smattering of silver coins in the straw, for which she wept and thanked the cruel God who had put her there in the first place.

Yes! There it was, the red-plumed hat of the king, and it was by the infirmary where Seneville and the other men from his party were kept. Oh merde, merde, Hubert tripped over his own unlaced boots, pressed his arms into his red sergeant's coat, and prayed his partisan was still by the lieutenant's sickbed. Half a hundred yards from the infirmary tent he straightened up, took a piece of bread from his forage sack, and made the pretense of having been about a breakfast stroll to look at the lines. As he arrived beneath the white awning, the king was saying, "Marvelous work. We've asked your colonel to make you the chief foraging party. That means your men will be given the Chevalier St. Michel in your place for the time being. So cheer up, hmm? You'll be back on the lines in no time and in the meanwhile your men won't get flabby." The king gave Prevert's belly a playful pat. Hubert could see a species of idiot pride glowing behind the man's eyes.

So much for rest! The chevalier St. Michel turned out to be a trim fop with only the vaguest idea of how to conduct himself on a battlefield. So it falls again to me, Hubert thought grimly, to manage this tide of metal and flesh. St. Michel took the men together in a big clump away from the camp and told them their objective: "There is a little fortalice not more than half a day's walk from here. The king wishes to drive his army in that direction, to surprise the Spanish in the big fort yonder." One of those huge ugly star-fortresses stood at the far end of a rolling field and meadow, a quarter mile distant. "But this means that the fortalice must fall so it does not serve as a caltrop in the heel of the Armée. So that is where we go today, mes amis!"

Hubert could have clubbed him senseless. St. Michel had the sure manner and waif-thin person of a dandy raised on horse-racing. Worse, he had a few dueling scars which showed him to be a man incapable of holding his tongue and even poorer at holding a sword. Sweet virgin, following this man into combat would be suicide. But follow they did, across field and dell, skirting a nameless little Dutch village and avoiding Spanish patrols on the raised roads. Hubert wondered if the world would miss the Netherlands were they to sink back into the sea. All the trouble they'd caused!

An hour or two after a hurried lunch they came to the fortalice St. Michel spoke of. It couldn't have housed more than twenty-five men all told but it was a strong position on top of a swell of land and the steep walls were capped with small culverins that could cut the flank of an army to pieces. St. Michel at least at the good sense to stop the party on the far side of a Dutch barn and hayloft before the fortress could sight them. When the farmers ran out to complain, Hubert managed to vent a little of his frustration with his commander by knocking the man down and threatening to break his leg with the butt of the partisan. That made him feel better.

"Are you ready, men?" St. Michel asked. They were most certainly not, clumped up in a group behind a barn. Hubert gave St. Michel one of the famed death glares that usually preceded flogging. St. Michel, insensitive to the normal operations of the army, threw up his hands. "What is it, sergeant?" His voice had the exasperated tone of noble officers everywhere.

Hubert folded his arms and tapped his foot. Some of the men grinned. Good old Hubert, going to give the pompous fool what he deserved. "We should arrange lines first, sir. And wait for the sun. In an hour or so, it will be in the gunner's eyes."

"Ah, yes, well," St. Michel fumbled, "yes. That sounds very good then."

Hubert rolled his eyes. Another day, another war.

Taking the fortress actually proved to be remarkably easy. The Spanish were caught completely off guard and the culverins never so much as fired a shot. Hubert spent the entire time trying to make sure St. Michel didn't get killed, throwing the idiot down when Spanish musket fire crackled from the hilltop and hauling him up when it was safe to charge. So much work for so little reward. Ah well. He would have to soon report some of the dead men, he mused as St. Michel strutted about the fortalice's little courtyard, crowing the victory. Otherwise the party would be so depleted as to risk its existence. Money was all to the good—surviving was better.

Hubert was in bad want of a musket. The nearest was eight yards away, where Gautier had been shot clean through the forehead, but it had fallen on the lip of the sunken road and was in plain sight to Spanish fire. "Conneries!" he swore at himself, at the world, at the Spanish, at his men. Lieutenant Seneville was moaning like a stuck pig with a ball in his arm and another one in his leg. His hat had fallen into the mud a mere handspan from Hubert; maybe he could grab it, fling it up, and then dive for the musket. Better, though, if he could just push Seneville into the woods and use him as a bargaining tool. Would the Spanish care to take a lieutenant captive in exchange for the lives of the other partisans? Well, he'd never get the chance to find out. The asses in charge of the column, most likely the colonel himself, had issued all sergeants with huge unwieldy partisans. What was he to do if he got corps-a-corps with a Spaniard? Knife him in the eye, perhaps, while all his men had the luxury of sabres and shot.

Just as he began to slither forward to make a grab at the weapon, the Spanish poured a hail of lead into the thicket. Bushes swayed madly back and forth and tree limbs whined with shot. The puffs of musket smoke rose in a thick choking cloud above the Spanish position. Hubert had had enough. "That's it, boys!" he growled, rising to his full and impressive height. His culottes were stained with the lieutenant's blood, but his men had no way of knowing that. To them he was like some kind of avenging colossus, bloody and proud. "Charge!" he howled. Over the lip of the road they went, their legs pumping to carry their bodies to the Spanish lines before the bastardes reloaded and turned them into so much useless meat.

The Spaniards, evidently, did not think well of their chances. With huge Hubert and his men screaming war cries and ploughing through the undergrowth and their own muskets still unloaded, the foe chose instead to make a tactical withdrawal. So what if that withdrawal had the appearance of a full route, some of the rearmost being sabred to death before they even managed to scramble up out of their hiding places? Hubert, with his ridiculous partisan in hand, never got as near as a handspan to one of the enemy, but it was his action that carried the day. He grinned and told his boys, "The king don't know what he has here in you." That was their work done for the time, and Hubert could hope that they wouldn't be sent out from the column in any other foolish action for a while again. Let them rest, and the lieutenant recover, let the other boys have their turn getting shot at or chopped to pieces.

With the wood secure, Hubert made a mental count of the dead. There was Gautier, of course, and two others. He'd keep Gautier on the payroll and add his own pension to the growing pool that Hubert himself collected and kept from the pay. When were they going to get their money? Probably not until the king captured another town or a party of partisans forced some Dutch to cough up their required taxes. The creditors in Paris were waiting in a line a mile long, and each new army action sent home gold and silver from the Spanish-held Dutch as the soldiers wrung it out of the populace.

Hubert was most concerned about Seneville out of all his lot. He was a lenient commander, and as the lieutenant of the partisan detachment from the Reg. de Lyonnais he was sergeant Hubert's direct superior. He never pried into things like the number of dead men against the number still alive to draw pay or the misappropriation of goods. Hubert had a small business on the side melting down extra shot and selling the lead to the Dutch for the repair of roofs damaged in the war. Gautier had been one of his chief confederates in that operation, which was all for the good because he'd been getting a little persnickety lately. Nothing put an end to a good career in the army like getting snitched out. Oh well. Au revoir, Gautier!

They returned to the column with Seneville on a makeshift stretcher, screaming every time one of the men jogged or jostled him. That left Hubert to make his report to the adjutant, which he did before going off to have a smoke and a fuck in the train. They'd been in the Netherlands for a year and a half now, and the fighting hadn't gone as Hubert had hoped. When he'd first signed on, scrawling his name on that sheet of paper as the drummer played patriotic rhythms and the recruiter had clapped him on the back and bought him a lager, he'd imagined standing up in one or two great setpiece battles, making his fortune from looting the dead, and taking the proceeds to buy a fine farm or some other business.

What had he got? Ten thousand Spanish forts, bogging down the army every step of the way. The clap once, and crabs. The whores that followed the Armée Royale were infinitely less clean than the farm-girls in neighboring villages. But the villages were Dutch and Lebeau had been caught just last week in a rick with some straw-haired lass and had his cock chopped off by her father and three Spanish soldiers before being sent stumbling back to the column, culottes all bloody from his excised organ, to show the French what happens to men who fuck little farm girls.

That was nothing, Alberte said. He was one of the old hands in the war, telling stories from all kinds of campaigns in Europe. He seemed to shave once a fortnight, perpetually stubbly was he. He also stank from refusal to bathe—"It'll rain soon enough, or the damn Dutch will bring the sea to us." It was a kind of fervent superstition. He told stories of Dutch Republican partisans breaking up dikes to flood out army positions and drown horses. "Yer lucky we ain't seen none a' that yet. But we will." We will, we will. That was Alberte's constant promise. Lucky we haven't seen the pox spread through the army... but we will, we will. This litany, this oration, was enough to drive you mad. That was part of the reason Hubert spent so much of his time among the camp followers. The other was, of course, that he had a purse swollen with the money of dead men and not enough ways to spend it. What good would it do to be a rich man only to have your face shot out the next day? No, better to lay with as many women as he could, drink as much as he could stomach, and pass out before the battle.

It was with shock and horror, then, that Hubert awoke to the sound of men acclaiming the king. Le roi de Soleil was present in his column. He scrambled out of his sweat-sodden sheets and tried to dress. The whore was little help to him, pawing at his naked ass and back, purring to receive his custom just once more. He glared at her and thought about striking her, but the ensuing fight would make him even later. For her part, she did her level best to please him and draw him back into bed just one more time—for she had a daughter and son in a village on the border who were in need of food and roofing. If Hubert had known, he might have paid her in stolen lead. As it was, his haste left behind a smattering of silver coins in the straw, for which she wept and thanked the cruel God who had put her there in the first place.

Yes! There it was, the red-plumed hat of the king, and it was by the infirmary where Seneville and the other men from his party were kept. Oh merde, merde, Hubert tripped over his own unlaced boots, pressed his arms into his red sergeant's coat, and prayed his partisan was still by the lieutenant's sickbed. Half a hundred yards from the infirmary tent he straightened up, took a piece of bread from his forage sack, and made the pretense of having been about a breakfast stroll to look at the lines. As he arrived beneath the white awning, the king was saying, "Marvelous work. We've asked your colonel to make you the chief foraging party. That means your men will be given the Chevalier St. Michel in your place for the time being. So cheer up, hmm? You'll be back on the lines in no time and in the meanwhile your men won't get flabby." The king gave Prevert's belly a playful pat. Hubert could see a species of idiot pride glowing behind the man's eyes.

So much for rest! The chevalier St. Michel turned out to be a trim fop with only the vaguest idea of how to conduct himself on a battlefield. So it falls again to me, Hubert thought grimly, to manage this tide of metal and flesh. St. Michel took the men together in a big clump away from the camp and told them their objective: "There is a little fortalice not more than half a day's walk from here. The king wishes to drive his army in that direction, to surprise the Spanish in the big fort yonder." One of those huge ugly star-fortresses stood at the far end of a rolling field and meadow, a quarter mile distant. "But this means that the fortalice must fall so it does not serve as a caltrop in the heel of the Armée. So that is where we go today, mes amis!"

Hubert could have clubbed him senseless. St. Michel had the sure manner and waif-thin person of a dandy raised on horse-racing. Worse, he had a few dueling scars which showed him to be a man incapable of holding his tongue and even poorer at holding a sword. Sweet virgin, following this man into combat would be suicide. But follow they did, across field and dell, skirting a nameless little Dutch village and avoiding Spanish patrols on the raised roads. Hubert wondered if the world would miss the Netherlands were they to sink back into the sea. All the trouble they'd caused!

An hour or two after a hurried lunch they came to the fortalice St. Michel spoke of. It couldn't have housed more than twenty-five men all told but it was a strong position on top of a swell of land and the steep walls were capped with small culverins that could cut the flank of an army to pieces. St. Michel at least at the good sense to stop the party on the far side of a Dutch barn and hayloft before the fortress could sight them. When the farmers ran out to complain, Hubert managed to vent a little of his frustration with his commander by knocking the man down and threatening to break his leg with the butt of the partisan. That made him feel better.

"Are you ready, men?" St. Michel asked. They were most certainly not, clumped up in a group behind a barn. Hubert gave St. Michel one of the famed death glares that usually preceded flogging. St. Michel, insensitive to the normal operations of the army, threw up his hands. "What is it, sergeant?" His voice had the exasperated tone of noble officers everywhere.

Hubert folded his arms and tapped his foot. Some of the men grinned. Good old Hubert, going to give the pompous fool what he deserved. "We should arrange lines first, sir. And wait for the sun. In an hour or so, it will be in the gunner's eyes."

"Ah, yes, well," St. Michel fumbled, "yes. That sounds very good then."

Hubert rolled his eyes. Another day, another war.

Taking the fortress actually proved to be remarkably easy. The Spanish were caught completely off guard and the culverins never so much as fired a shot. Hubert spent the entire time trying to make sure St. Michel didn't get killed, throwing the idiot down when Spanish musket fire crackled from the hilltop and hauling him up when it was safe to charge. So much work for so little reward. Ah well. He would have to soon report some of the dead men, he mused as St. Michel strutted about the fortalice's little courtyard, crowing the victory. Otherwise the party would be so depleted as to risk its existence. Money was all to the good—surviving was better.

Thursday, February 20, 2014

Maps are Liars

This is a subject I've talked about before at some length, but I always like to revisit it. Namely that maps, especially those drawn before the 17th century, have been more representative and ideological than realistic with proper distances mapped upon them. Indeed I cannot think, off the top of my head, of any map that was used as a navigational tool prior to the 17th century. Most of them were in fact ways of demonstrating sacred geography (the T-circle map with Jerusalem at the center, for example). Not being well-schooled in medieval navigation, this begs the question of how ships found their way to where they were going without a good, accurate, vision of what the shores looked like, how pilgrims managed to get successfully from one city to another, and things of that nature. I don't know the answer to that yet, though I intend to start investigating it now that the idea has come into my head.

More importantly for this discussion, maps that players look at don't really have to be accurate. I've been brutally murdering myself for years over how to produce a series of accurate maps that remain accurate at all levels. This has driven me to make files with massive resolutions, to add minute details, generally to go crazy. I've made worldmaps, hexmaps, regional maps, town maps. I've crashed computers with the files I've asked them to handle so I could be sure that when I zoomed in, features wouldn't change places.

And yet, and yet—the maps available to a PC and the mental image they would have of their world... are probably not even half as good as the maps I've been struggling to produce. On the other hand, we are dealing with a fictional world that we're asking other people to inhabit with their minds. There is a reason that many fantasy novels begin with one important thing, before there is even a story on the page, and that is a map. How difficult is it to place oneself beside oneself and into a new, nonextant, land, to hold the notion of an unreal place within themselves and convince themselves that they can see it? VERY. So maps serve a useful and important purpose. To relegate them merely to the status of cultural relics wherein players cannot be certain of the actual shape of the world (or, more accurately, players can only understand the world as their characters do, requiring yet another level of commitment on top of what is already a staggering amount of mindwork we ask them to do) is a dangerous question for those who wouldn't breach the verisimilitude and play environment. What, then, are we to do?

Clearly the maps must have some utility, as well as appeal, for them to work. But they do not need to have the utmost utility. They can be wrong in places, or the scale can be off without causing a player meltdown. More importantly, there are many things that would not show up on these maps of theirs. Certain ruins, for instance. Bandit camps, hidden dwarven holds, and all manner of goblin and orcish settlements. Which is not to say they cannot add them to the map as they go, a time-honored tradition of marking the conquests of a party.

Maps are something we must treat with care, lest we on the one hand drive ourselves (as I have) insane with trying to keep them as accurate as possible or on the other make it impossible for players to understand the layout of their world.

More importantly for this discussion, maps that players look at don't really have to be accurate. I've been brutally murdering myself for years over how to produce a series of accurate maps that remain accurate at all levels. This has driven me to make files with massive resolutions, to add minute details, generally to go crazy. I've made worldmaps, hexmaps, regional maps, town maps. I've crashed computers with the files I've asked them to handle so I could be sure that when I zoomed in, features wouldn't change places.

And yet, and yet—the maps available to a PC and the mental image they would have of their world... are probably not even half as good as the maps I've been struggling to produce. On the other hand, we are dealing with a fictional world that we're asking other people to inhabit with their minds. There is a reason that many fantasy novels begin with one important thing, before there is even a story on the page, and that is a map. How difficult is it to place oneself beside oneself and into a new, nonextant, land, to hold the notion of an unreal place within themselves and convince themselves that they can see it? VERY. So maps serve a useful and important purpose. To relegate them merely to the status of cultural relics wherein players cannot be certain of the actual shape of the world (or, more accurately, players can only understand the world as their characters do, requiring yet another level of commitment on top of what is already a staggering amount of mindwork we ask them to do) is a dangerous question for those who wouldn't breach the verisimilitude and play environment. What, then, are we to do?

Clearly the maps must have some utility, as well as appeal, for them to work. But they do not need to have the utmost utility. They can be wrong in places, or the scale can be off without causing a player meltdown. More importantly, there are many things that would not show up on these maps of theirs. Certain ruins, for instance. Bandit camps, hidden dwarven holds, and all manner of goblin and orcish settlements. Which is not to say they cannot add them to the map as they go, a time-honored tradition of marking the conquests of a party.

Maps are something we must treat with care, lest we on the one hand drive ourselves (as I have) insane with trying to keep them as accurate as possible or on the other make it impossible for players to understand the layout of their world.

Wednesday, February 19, 2014

In the Court of the Crimson King

|

| Who is this guy? He's a creep. |

Here is my prospectus on a Court of the Crimson King as a setting (as usual, envisioned for FG&G, though it's mostly rules agnostic. If there's an outcry I'll start statting things up):

The world is a decaying, baroque place. There are lands outside of Corolaine but they are of little consequence to us. Corolaine is thus, for our citizenry, the world. There are mountains and seas that girdle her and three moons that circle one another in her sky. Her state is late medieval, replete with paper and installed bureaucrats but still focused around the king's personal curia. Outlaws, prisoners, and dissenters against the thousand-year-reign of the King are placed upon the flying prison ships that convey them skyward ever after. This is Corolaine, home of the Crimson King. Cochin City, where the Court is located, is the heart of the kingdom.

The Crimson King and the Black Queen. These are the two nominal rulers of Corolaine, though the King has done little in the past three hundred years to merit the title. He is an exhausted old man, always present at court with his long white hair and scraggly beard, resplendent in the crimson gown and crown of gold. Most of the affairs of state are dealt with by Nocta, the so-called Black Queen, and King Rufus' fifth wife. Each month she celebrates anew the death of the Princes Alax and Tefer in the endless war with the kingdom of Laudria upon Corolaine's southern border.

Nocta, the Black Queen, is also the matriarch of the House of Nix. This is one of the political factions in Cochin City and currently the most powerful.

Clovis, Keeper of the Keys. A minor magician, Clovis is the Keywarden of Cochin City. His job it is to make certain that no foul alchemist or necromancer grows in power in the shadow of the Court. He uses his lesser magical talent to sniff them out and report them. In addition he is the leader of the civil militia (though he must still answer to the Crimson Knights). Clovis and the Black Queen do not get along very well, and he considers himself unbendingly loyal to King Rufus (though he would likely sell the king out to safe his own life).

The Schola Cochenum. This pilgrim house stands near the great keep of Cochin and services all those traveling to the city for religious reasons. The cult of the Crimson King has been thriving these past four or five hundred years, and as the nine-hundredth anniversary of the thousand-year-reign approaches more and more pilgrims flood the Schola seeking to do homage.

The Fire Witch. One of the members of the House of Nix, the Fire Witch (also known as Pyrréah) is the right-hand of Nocta, the Black Queen. She has a great deal of mastery over that element and is a feared enforcer of the House of Nix. However, she cannot long remain in Corolaine; her own estates, both mundane and arcane, require tending. Only by sounding the tongueless cracked brass bell in the ancient way may she be brought back to the court, and then only for a fortnight at a time.

The Purple Piper. One of the many Court Servants, the Piper wears comic attire and carries his recorder with him where'r he goes. He is a cunning strategist of the court and also a Count of Baran—he is the patriarch of that house, and leader of the Barani faction at court. What they desire is unknown, besides stability and the continued reign of the King.

The Pattern Juggler. A wizard of moderate power, the Pattern Juggler is also amongst the Court Servants. He is the eyes and ears of the House of Cashal, which is interested only in its own preservation. While the Purple Piper retains command of the choirs which sing the king to sleep each night, the Patter Juggler's prime domain is that of the orchestra of Players who rouse him each morning.

The Grinding Wheel. Legend and rumor tie the ancient grinding wheel at the foot of the throne to the very life of the monarch himself. It is said that the thousand-year-reign of the Crimson King will come to an end when this mystic wheel, originally granted to the court by the mysterious Gardener in the dawn of the Crimson King's rule, finally stops spinning. No known force can keep it in place, and it is said that one can even grind gold or diamonds beneath its rough surface.

Prism Ships and the Prison Moons. Prism ships are great galleons with prismatic rudders that leave a strange scent and taste on the air. They fly high above Corolaine, laden with prisoners who are exposed on deck to the rays of one of the Prison Moons. High in the atmosphere, this light forms bonds that are unbreakable except by direct exposure to sunlight. Part of the reason Corolaine will never be conquered is its vast fleet of prism ships that are ready, at a moment's notice, to defend the realm.

The Yellow Jester. The least of the Court Servants and the least powerful, personally, the Yellow Jester is said by some envious fools to rule the entire kingdom by pitting one family against another and whispering his poison in the king's ear.

Tuesday, February 18, 2014

Telescoping the Middle Ages

STOP. Don't haphazardly combine things from 500 to 1500 into a single setting or story or image. It's been done, and it isn't pretty. We have a tendency to compress time periods that are farther away from us, rolling them all together. We would never dream of mixing the 40s and the 70s because those decades are so distinct to us. Because of their distance, the 1100s and the 1300s might appear to be interchangeable in terms of philosophies, modes of dress, architecture, you name it. But they aren't. If you're going to start combining things from various periods, at least be aware of what you're doing.

Here's a good place to start. That's the wikipedia category for medieval costume, where you can look at a period (usually lumped into a hundred-year group, so we still have to do some telescoping) and get a feel for its clothing. You'll notice that the changes are actually rather marked. A tunic is not a tunic is not a tunic, as it were. There is detail there to explore and mashing together different periods without really being aware of what you're doing sacrifices that detail for no real reason (and makes those people who know the difference cringe curiously).

For that matter, stop depicting shields of any type as being solid metal plates. At best they were covered in a thin layer of metal but were 90% simply wood with leather over them and a metal boss and rim. No one ever used a solid metal shield. No one. Don't do it. The only reason to depict a shield that way is ignorance and now you can't even lay claim to that defense anymore because I just told you.

And if you're thinking that because you're doing fantasy it doesn't matter, maybe you shouldn't be doing fantasy anymore. Or else stick to pulp stuff. Because honestly, how serious can you be if you don't care?

Here's a good place to start. That's the wikipedia category for medieval costume, where you can look at a period (usually lumped into a hundred-year group, so we still have to do some telescoping) and get a feel for its clothing. You'll notice that the changes are actually rather marked. A tunic is not a tunic is not a tunic, as it were. There is detail there to explore and mashing together different periods without really being aware of what you're doing sacrifices that detail for no real reason (and makes those people who know the difference cringe curiously).

For that matter, stop depicting shields of any type as being solid metal plates. At best they were covered in a thin layer of metal but were 90% simply wood with leather over them and a metal boss and rim. No one ever used a solid metal shield. No one. Don't do it. The only reason to depict a shield that way is ignorance and now you can't even lay claim to that defense anymore because I just told you.

And if you're thinking that because you're doing fantasy it doesn't matter, maybe you shouldn't be doing fantasy anymore. Or else stick to pulp stuff. Because honestly, how serious can you be if you don't care?

Monday, February 17, 2014

More 7th Sea: The Pazo

As I was planning some stuff in Castille (the common language of the PCs and the nationality of one and a fourth of them), I realized that I really had no idea what Spanish manor houses look like aside from what I've gathered thinking about ranchos in California. That's not really how I like to go about things, so I started to do a little research.

The manor houses of Galicia are known as "pazos," a cognate with palace. I can't find a lot of information about them online, but it's clear they share some elements with the English manorhouse of the 17th-18th centuries though they appear to be much more formidable in terms of defense.

The manor houses of Galicia are known as "pazos," a cognate with palace. I can't find a lot of information about them online, but it's clear they share some elements with the English manorhouse of the 17th-18th centuries though they appear to be much more formidable in terms of defense.

The actual historical analogues of Castille are Galicia, Leon, Navarra, and (surprise!) Castile. Like all else in the 7th Sea world, the history of Spain has been simplified to reduce the hideous complexity of the past. I've yet to find any good maps of the layout of the pazos.

This brings me to a second point about 7th Sea—namely, a lot of information is missing from the books. For example, I've never seen a list of prices for cargo anywhere, nor for the food required to feed crew members on a ship. The governments of the various nations and their nobility are only vaguely elaborated even in the kingdom sourcebooks. It's unclear whether or not the Castillian title "Don," for instance, refers only to the governors of the huge Ranchos or to all landed nobility—or indeed if there even are lesser nobility in that sense, as the Castille sourcebook refers to gubenadores and caballeros but never any mention of those running individual towns and estates.

I've simply decided to call them "Don" as well.

Friday, February 14, 2014

Fiction Friday: The Fiction of Yesteryear

What's that, you say? You need an index of all the stories that have been on the Frothing Mug with brief descriptions of each? VERY WELL!

The Battle of Crestley—A tenth age tale of ships and valor off the southern shore

Beyond the Hedge: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, and part 6—The story of Barley Hedgeman and his adventures before he became a porter for a 10th Age adventuring party

Bury This Letter Deep—A tale of revenge set during the Continental Army's winter at Valley Forge

Le Dieu Perdu—Love, hate, and Paris in the 17th century

Flashman and the Gods of Mars: part 1—ongoing, the continuation and finale of Flashman as mixed with the Space 1889 Setting

The Hired Blade, part 1 and part 2—The duelist Giancarlo in Romania amongst the Romani

Going Home—A short short in honor of Ray Bradbury

The Masque of Faith—A Giancarlo story about the famous duelist and his fight in Rome

The Mirrors of Chelyabinsk—A young man is sent on his first commission to Chelyabinsk and discovers a dark secret of cold Siberia.

The Peddler and the Swine and Part Two—An incomplete 12th century story about Schweinfurt featuring whiffs of paganism and mystery

The Pillars of Hercules—Another Giancarlo tale, about his duel in the Straits of Gibraltar

The Reservation: part 1, part 2, and part 3—A futurist tale about the eco-reservations, the City, and someone breeding illicit meats in the far future.

The Second Transformation of the Butterfly—The story of Szprinca the bird-killer in the 19th century Pale of Settlement.

Le Sergent—In which Sergent Hubert receives a new commander and his chronicle begins.

The Siege—Giancarlo fights in the Turko-Venetian war!

The Battle of Crestley—A tenth age tale of ships and valor off the southern shore

Beyond the Hedge: part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, and part 6—The story of Barley Hedgeman and his adventures before he became a porter for a 10th Age adventuring party

Bury This Letter Deep—A tale of revenge set during the Continental Army's winter at Valley Forge

Le Dieu Perdu—Love, hate, and Paris in the 17th century

Flashman and the Gods of Mars: part 1—ongoing, the continuation and finale of Flashman as mixed with the Space 1889 Setting

The Hired Blade, part 1 and part 2—The duelist Giancarlo in Romania amongst the Romani

Going Home—A short short in honor of Ray Bradbury

The Masque of Faith—A Giancarlo story about the famous duelist and his fight in Rome

The Mirrors of Chelyabinsk—A young man is sent on his first commission to Chelyabinsk and discovers a dark secret of cold Siberia.

The Peddler and the Swine and Part Two—An incomplete 12th century story about Schweinfurt featuring whiffs of paganism and mystery

The Pillars of Hercules—Another Giancarlo tale, about his duel in the Straits of Gibraltar

The Reservation: part 1, part 2, and part 3—A futurist tale about the eco-reservations, the City, and someone breeding illicit meats in the far future.

The Second Transformation of the Butterfly—The story of Szprinca the bird-killer in the 19th century Pale of Settlement.

Le Sergent—In which Sergent Hubert receives a new commander and his chronicle begins.

The Siege—Giancarlo fights in the Turko-Venetian war!

Thursday, February 13, 2014

A Real Adventure Site—Ani, Capital of the Kingdom of Armenia

If you're interested in some photographs of what a real adventure site of ruins and mystery might hold, one that is at least semi-European in style as opposed to North African or mostly middle eastern, take a look at the remains of the ancient city of Ani...

Between 961 and 1045 it was the capital of the medieval (Bagratuni) Armenian Kingdom that covered much of present day Armenia and eastern Turkey. The city is located on a triangular site, visually dramatic and naturally defensive, protected on its eastern side by the ravine of the Akhurian River and on its western side by the Bostanlar or Tzaghkotzadzor valley. The Akhurian is a branch of the Araks River and forms part of the current border between Turkey and Armenia. Called the "City of 1001 Churches," Ani stood on various trade routes and its many religious buildings, palaces, and fortifications were amongst the most technically and artistically advanced structures in the world.

At its height, Ani had a population of 100,000–200,000 people and was the rival of Constantinople, Baghdad and Damascus. Long ago renowned for its splendor and magnificence, Ani was abandoned and largely forgotten following the earthquake of 1319.

—From the Wikipedia Entry

Wednesday, February 12, 2014

Command and Control

Adventure stories don't have random encounters. What? Yes, you heard right. Anything anyone sees in a novel is specifically shaped to give some impression, to build story, or to reveal elements of character. Nothing can be random, because everything is planned by the author. The same goes for 7th Sea—there is no system in place for random encounters. When the GM feels like there should be an encounter, there is one. When the GM needs an encounter to happen, it does. This is a fantastic opportunity to slip into the dreaded illusionism that has been so well illuminated by the OSR for indeed, the method of fiat encounter and "story development" runs the risks of utterly destroying the all-important freedom of choice of the player. What, then, is a good GM to do?