Having started to watch the excellent David Simone show The Wire for the first time last week (I'm now in Season 4, if that gives you any idea of how much time I spend watching it). The complexity of the show stands out as a beacon in the night of television; The Wire has effectively created a city of its own, a mirror-Baltimore that has its own ins and outs. What does this mean for D&D? I've been thinking about that and, after some study and serious pondering, I believe that The Wire has a lot to teach us about making realistic cities in Dungeons and Dragons.

1) Cities are complex. This can be extended out to any organization. The amount of infighting, backchannel backstabbing, and political faction-playing in the show is a great lesson. Adventurers are generally hired by someone right? The people who hire them are, generally (at least in my experience), given little more fleshing out than the police department in a regular cop drama. I have tried my best over the past few years to make sure every job is charged with consequence, with political backlash. After watching The Wire I have a thousand more ideas on how to detail the people (and organizations) that hire adventurers.

2) Shit is difficult to accomplish. This translates less to D&D because the organizational inertia which prevents the successful accomplishment of various police tasks doesn't necessarily exist in a fantasy world. In a medieval world there are few institutions that can drag you down in that manner—but that doesn't mean that political interests can't do the same. Of course, The Wire is a show and D&D is a game: you don't want to prove to the players that it is always or even generally impossible to succeed due to institutional (or in this case perhaps political) circumstances. That would quickly get demoralizing. However, the option should always be there and I personally like to draw out unforeseen consequences of even the most goodly acts.

3) Characters aren't good or evil. Uh oh, the ALIGNMENT TALK. Here again, I'm not saying that good or evil are not applicable. Good and evil, in alignment terms, are descriptions of the way a character behaves. But, as The Wire teaches us, no one always behaves in a certain way all the time. Alignment lenience here is important. Not every Lawful Good man's actions are going to be lawful good forever. That doesn't mean that, because of a few breaks with alignment, that you're alignment is going to change. Of course, consistent breaks speak of a character change. So here I don't mean characters aren't good or evil (in terms of alignment), what I mean is that people aren't bad people or good people.

4) People have long memories. Chances are, if adventurers screw with someone at some point, that person will remember. Sometimes, you do something nasty to a local knight only to discover that he's been named the Seneschal of the Emperor. This stuff sticks with you. Conversely, do a good turn for someone and you never know when they might turn up again to help you out.

5) Everything is connected. The crime network in The Wire is contiguous, connected, and spreads like an insidious cancer throughout every organ of government in Baltimore. Why should crime in a fantasy city be different? Everyone is connected to everyone else, somehow. It's the DMs job to figure out how they are and the PCs to exploit it (or be exploited by it).

Tuesday, January 29, 2013

Monday, January 28, 2013

Demons and Devils and Prison Stones

One of the lasting legacies of the Scholastic period of the Second Empire was the codification of demonology into a discreet and arcane discipline. Before the Schools, demonological magic was a scattering of traditions and folk-knowledge that had no real boundaries. Demonology was said to be widely practiced in ancient Zesh, but that art was lost as the southmen fled to Arunia (or rather was only maintained in the most haphazard of ways).

Second Empire tradition says that the demons and devils of the Nine Hells found their way there (and their respective homes in the 5th and 6th Hell respectively) by following a demon-prince of great power. They settled there, within the scope of Arunia's Three Worlds, and ever after have poured into the lower two realms like locusts. They still cannot bridge the gap to the Middle World without assistance (for the most part) which makes demonology one of the few ways to bring a creature from the Lower World to Atva-Arunia.

Today, of course, the demonological lore of the Second Empire is mostly lost. What remains are the few spells and bits of knowledge that survived the collapse of the Schools and the wars of the various magi, which weakened both the magical tradition of the Second Empire as well as the empire itself. Like the lost art of the Tekhne Manuscripts, there is much from that period in terms of fiendish knowledge that has been lost to the mists of time.

A not uncommon use for that Second Empire knowledge was to bind demons and devils to fetish-like charms so that they may be forced into service by the sorcerers of one School or another. While this practice began with simple wands and ivory sticks, the ultimate expression of the art form was realized in the enchanted gems known as Prison Stones.

The Prison Stones were gemstones of uncommon worth that were wrapped about with magical writing and graven in Maidic runes. Hundreds of spells may be laid upon a single stone to protect it from the ravages of the demon imprisoned within or the forces of nature that might contrive to act on it from without. Many of these stones were made hard as ædrite so they would never be subject to destruction by force, thus freeing their occupant.

The stones, storing a fiendish essence, could be used to force the creature to manifest and do the bidding of the wielder or, in the hands of a sorcerer familiar with their power, harnessed to the wielder's own magical might to make them even more formidable. Yet, they represent a great source of danger to the uninitiated: the spirit within the stone would stop at nothing to convince its carrier to unweave the magic around it and give it freedom. Some of the more powerful fiends (notably, for one, the creature called Iorlex) where fond of offering to fulfill a single wish for their freedom.

In the modern age of Arunia, the stones are mostly lost. Many of their magics have been weakened so that some of the Prison Stones might even be destroyed by mundane means, freeing their occupants. Knowledge of their use is limited to a few ancient manuscripts, none of which are easily accessible. So, these powerful stones lie in shallow graves where imperial wizards fell, or locked deep inside vaults for safe keeping, or perhaps tucked away in a ruined niche of some old imperial garrison. Though there were never more than five or six hundred at any given time, the stones themselves do not lie idle and it is thought that they may be able to call people to them with a silent, siren song.

The most recent surfacing of one of these Prison Stones was set in the blade Heartcleaver by a dwarf of Portomagno, who himself murdered the sorcerer that discovered it. The blade, once claimed by the unfortunate adventurer Hegoro Beloro, proved too much for him and overcame him with its grating ego, forcing him to subsist in the dwarven crypt on the flesh of the dead while preventing him from leaving for fear of the things the blade would make him do.

An interesting but important fact: though the blade contained the stone of Iorlex, it itself had a personality altogether divorced from the demon and was petrified of the thought that its stone would be destroyed. Indeed, without it Heartcleaver was simply a grotesquely ornate bastard sword. Once Iorlex was freed (and subsequently banished) the blade knew no more.

Second Empire tradition says that the demons and devils of the Nine Hells found their way there (and their respective homes in the 5th and 6th Hell respectively) by following a demon-prince of great power. They settled there, within the scope of Arunia's Three Worlds, and ever after have poured into the lower two realms like locusts. They still cannot bridge the gap to the Middle World without assistance (for the most part) which makes demonology one of the few ways to bring a creature from the Lower World to Atva-Arunia.

Today, of course, the demonological lore of the Second Empire is mostly lost. What remains are the few spells and bits of knowledge that survived the collapse of the Schools and the wars of the various magi, which weakened both the magical tradition of the Second Empire as well as the empire itself. Like the lost art of the Tekhne Manuscripts, there is much from that period in terms of fiendish knowledge that has been lost to the mists of time.

A not uncommon use for that Second Empire knowledge was to bind demons and devils to fetish-like charms so that they may be forced into service by the sorcerers of one School or another. While this practice began with simple wands and ivory sticks, the ultimate expression of the art form was realized in the enchanted gems known as Prison Stones.

The Prison Stones were gemstones of uncommon worth that were wrapped about with magical writing and graven in Maidic runes. Hundreds of spells may be laid upon a single stone to protect it from the ravages of the demon imprisoned within or the forces of nature that might contrive to act on it from without. Many of these stones were made hard as ædrite so they would never be subject to destruction by force, thus freeing their occupant.

|

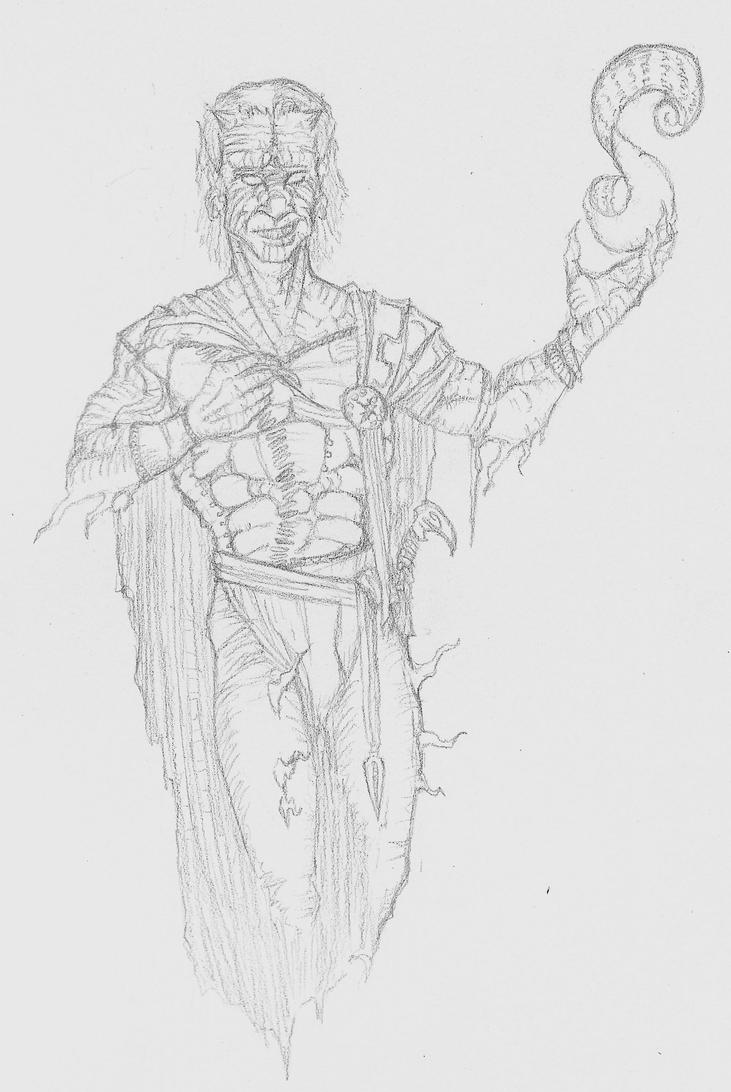

| Iorlex |

In the modern age of Arunia, the stones are mostly lost. Many of their magics have been weakened so that some of the Prison Stones might even be destroyed by mundane means, freeing their occupants. Knowledge of their use is limited to a few ancient manuscripts, none of which are easily accessible. So, these powerful stones lie in shallow graves where imperial wizards fell, or locked deep inside vaults for safe keeping, or perhaps tucked away in a ruined niche of some old imperial garrison. Though there were never more than five or six hundred at any given time, the stones themselves do not lie idle and it is thought that they may be able to call people to them with a silent, siren song.

The most recent surfacing of one of these Prison Stones was set in the blade Heartcleaver by a dwarf of Portomagno, who himself murdered the sorcerer that discovered it. The blade, once claimed by the unfortunate adventurer Hegoro Beloro, proved too much for him and overcame him with its grating ego, forcing him to subsist in the dwarven crypt on the flesh of the dead while preventing him from leaving for fear of the things the blade would make him do.

An interesting but important fact: though the blade contained the stone of Iorlex, it itself had a personality altogether divorced from the demon and was petrified of the thought that its stone would be destroyed. Indeed, without it Heartcleaver was simply a grotesquely ornate bastard sword. Once Iorlex was freed (and subsequently banished) the blade knew no more.

|

| Hegoro Beloto, the Bastard of Belladon |

Thursday, January 24, 2013

Running the Household: Bailiffs and Stewards

Medieval themed fantasy would have you believe that every land has a lord, and that every lord has but one land. Each town or vill has its baron, its great man with heraldry and shields and knights and all that jazz. Of course, this couldn't be farther from the truth and no lord would ever have been able to raise enough men to do battle with if every holding in the land was subdivided into a thousand thousand petty lordlings. Certainly, there were subdivisions, but it was a rare enough case when each lord owed fealty to both a higher and lower lord. The real questions are: If a lord owns several towns, vills, and manors, who administers all of them? Where is he, if that manor house has no lord living in it? Who DOES live in it?

The answer is fairly simple. Every little town might have a manor house, and it is true that there were lords that owned multiple manors. The man living in that manor, then, was less likely the lord (by the law of numbers, since there were more manors than lords) and more likely his local bailiff. Bailiffs in England were drawn from the populace of the town they administered and were often wealthy or highly placed farmers, knights, or lesser sons of other houses. The bailiff generally served as the ultimate legal authority save the lord himself and was sometimes attended by a serjeant of his own. It was highly unlikely that a baron would have barons of his own to attend him, something important to remember once your baron rules over several towns. His arm of the law there would be the bailiff.

The bailiff was also in charge of the collection of rents and overseeing of pretty much all the towns functions. This included, of course, supporting the asshole miller (everyone always hated the miller, who was part of the lord's monopoly on gristing and milling), making sure roads and bridges were kept up and collecting market tolls (if there were weekly or monthly markets in the town or vill).

The steward was his other administrative ally (apart from the reeve, not addressed here) who was generally a literate knight (or one with a secretarius clerk) that would perambulate to check the lord's holdings and ensure that all was being dealt with in a manner that would bring him increase and wealth. If tubs of butter or barrels of malt were lacking in a villages taxes, the steward would go and investigate not the lord. Bailiff (and town reeve) would be responsible for reporting to the steward and helping him solve the matter until he returned to the seat of the barony.

So, when you're designing small manorial vills and outlying villages, there's no need to give them their own heraldry (though the bailiff might have his own arms) and their own baron. Indeed, a baron would generally be very insulated from the regular populous on most occasions save feast days. Whether or not the nobles delight in meeting the adventurers they hire is another question, but I'd bet that most would at least make preliminary contact by their local bailiff or steward. The same goes on a grander scale with important nobles maneuvering against one another: they are unlikely to make contact directly or even indirectly through their spy masters, likely preferring some intermediary agent that could never be tied back to them.

The answer is fairly simple. Every little town might have a manor house, and it is true that there were lords that owned multiple manors. The man living in that manor, then, was less likely the lord (by the law of numbers, since there were more manors than lords) and more likely his local bailiff. Bailiffs in England were drawn from the populace of the town they administered and were often wealthy or highly placed farmers, knights, or lesser sons of other houses. The bailiff generally served as the ultimate legal authority save the lord himself and was sometimes attended by a serjeant of his own. It was highly unlikely that a baron would have barons of his own to attend him, something important to remember once your baron rules over several towns. His arm of the law there would be the bailiff.

The bailiff was also in charge of the collection of rents and overseeing of pretty much all the towns functions. This included, of course, supporting the asshole miller (everyone always hated the miller, who was part of the lord's monopoly on gristing and milling), making sure roads and bridges were kept up and collecting market tolls (if there were weekly or monthly markets in the town or vill).

The steward was his other administrative ally (apart from the reeve, not addressed here) who was generally a literate knight (or one with a secretarius clerk) that would perambulate to check the lord's holdings and ensure that all was being dealt with in a manner that would bring him increase and wealth. If tubs of butter or barrels of malt were lacking in a villages taxes, the steward would go and investigate not the lord. Bailiff (and town reeve) would be responsible for reporting to the steward and helping him solve the matter until he returned to the seat of the barony.

So, when you're designing small manorial vills and outlying villages, there's no need to give them their own heraldry (though the bailiff might have his own arms) and their own baron. Indeed, a baron would generally be very insulated from the regular populous on most occasions save feast days. Whether or not the nobles delight in meeting the adventurers they hire is another question, but I'd bet that most would at least make preliminary contact by their local bailiff or steward. The same goes on a grander scale with important nobles maneuvering against one another: they are unlikely to make contact directly or even indirectly through their spy masters, likely preferring some intermediary agent that could never be tied back to them.

Friday, January 18, 2013

Play Report: Ethnography of the Virgin Blades

Last night was my first in-person D&D session in an eon. It was the first D&D session of any type for two of my players, a coworker and an (ex)coworker (long tale of betrayal and assholes behind that transformation). Jocelyn played as well, as did Frank—a long time veteran of the game who has still, if I am not mistaken, not played a live session of D&D in more than two years and even then the last two or three beyond that were played with me alone in one-on-one games. It went pretty well, I think, and the two newcomers acquitted themselves admirably.

As there were three elves from the Greatwood in the party, I thought it best to simply help them spin a rapid backstory involving their working together on a caravan as hired guards, explaining the handful of gold they had with them upon beginning play. They have traveled for some three to five months to arrive in Valbois. Ricki, playing a Priest of Eleia, had simply spent her (his, she's playing Antonio, a half-Dorl) in the town of Casselflor being trained on the grounds of the Eliean temple.

They started in the Casselflor marketplace, looking for a tavern. Such is always the way of adventurers, new or old, it seems. As their eyes alit upon a low thatch-roofed building with a sign over the door displaying a black tun of ale painted on its board, they also noticed a man approaching to head them off—the hefty broad-shouldered representative of the baron (the Eylic word being "shire reeve," or sheriff, the Varan "bailiff") Sieur Guion de Flor. Sieur Guion explained that he was looking to hire up some adventurers to discover what was happening to the farmer's livestock; apparently, vanishing. Whether or not the disappearance of a local boy from Battle Farm (Henshel, according to Ricki who made a name up for him on the spot) was related, the knight couldn't say.

So, agreeing to return to his manse with information in order to get 120 golden pillars (fulcre or ƒ as Varan orthography would have it -- Varan coinage is written in this manner: 120ƒ {gp, fulcre}, 120t {sp, turre}, 120s {cp, scutari}) the group set off. Antonio provided them with some much needed guidance about the local farms, but not before Sieur Guion left them his parting words: Farmer Balduin Bramble, tenant of Bramble Farm against the northern verge of the Vallain Wood, believed that the whole situation was caused by the ghost of a famous bandit.

The party went inside to drink and discuss their options. They asked little of the Black Keg's barkeep, Aldrus, save for a pitcher of his local beer. The four of them decided that they'd best ask Balduin Bramble some questions. This was done lickety split, so they finished up their cups of beer, swilled down what was left (or secretly poured it out into the rushes to splatter onto the floor) and hoofed it out of the town to the north.

Passing in the shadow of the grim ruin of the Florian keep hardly dampened their spirits, and before long they found themselves at the Bramble farm. A small cottage of unmortared river stone sheltered the old halfling with its wide porch and they joined him there, setting down in chairs nearby. He told tale after tale of the bandit Langrim the Blade, who had terrorized Casselflor back during the orc wars. He was convinced that the spirit of the bandit was stealing children to "replenish his own forces and ride again!" He told them they could play off Langrim's legendary vanity if they were to meet.

Cyosta (the party thief) meanwhile left to examine the fields and quickly found signs of passage on the freshly fallen snow. The party followed the trail into the woods and realized right quick it was leading to Glen Casse, the rumored bandits den of the orc wars. They spread out, leaving Antonio on the road with the party dogs (of which there are three: Caesar, Romeo, and Hephaestus) so they could slip quietly through the wood.

They discovered the hill-glade of Glen Casse and, seeing it empty, began to search it. A fire pit was at once evident, with the clear signs of chewed and gnawed bones amongst the ashes. As the entire party came to examine it, a blistering series of yaps and yips emerged from the hill, from behind a large rock. The party was under attack! They took cover behind nearby pine trees; both Antonio and Cyosta were struck by arrows before they could reach it.

Cyosta being the only party member with a ranged weapon, fired his bow up the hillside, loosing several arrows until he struck one of the kobolds that had appeared. The arrow took it through the eye and the other two immediately vanished behind the boulder. The party limped up after them to discover what they had feared: a warren of tunnels leading into the hill.

First the party argued about what to do for several minutes while the kobolds within organized. They debated smoking out the creatures, but were eventually afeard such actions would kill the boy (if he was truly in there). Cyosta determined to explore the rest of the hillside to see if there were other entrances. Before he could, however, Antonio healed him with a spell while Coi (the party fighter, Jocelyn) rushed into the sandy-floored cavern.

And straight into a trap, wherein four javelins were loosed at her. Batting them aside and bulling forward, she managed to reach the line of kobolds on the right while her dogs sank into the two on the left. They, of course, had emerged from tunnels that were out of sight from without, and a rapid heated battle ensued. On either side a kobold was killed while the other fled. This led to the most dreaded of situations: the split party.

I think I managed it fairly well, doing one round's worth of action with the left-hand group and one with the right. They split with Antonio and Coi together and Cyosta and Ovelaave (the elvish mage) on the other side, heading right-ways. The right-hand party blundered into a room of 9 kobold elite guards and 2 guard boars—which they had trouble distinguishing due to the low light leaving them only infravision to see by.

Ovelaave busted out his one spell (a judicious color spray) knocking out six kobolds, stunning the warthogs, and causing the rest of the creatures to flee. Murder ensued.

On the other side, Coi and Antonio unknowingly encountered and killed Skarax the Kobold King and his two guards before pressing on. The groups met together again in the breeding warren where they dispatched the remaining kobold females and young. Thus ended the first ever session of the virgin blades (they will probably hate that name).

As there were three elves from the Greatwood in the party, I thought it best to simply help them spin a rapid backstory involving their working together on a caravan as hired guards, explaining the handful of gold they had with them upon beginning play. They have traveled for some three to five months to arrive in Valbois. Ricki, playing a Priest of Eleia, had simply spent her (his, she's playing Antonio, a half-Dorl) in the town of Casselflor being trained on the grounds of the Eliean temple.

They started in the Casselflor marketplace, looking for a tavern. Such is always the way of adventurers, new or old, it seems. As their eyes alit upon a low thatch-roofed building with a sign over the door displaying a black tun of ale painted on its board, they also noticed a man approaching to head them off—the hefty broad-shouldered representative of the baron (the Eylic word being "shire reeve," or sheriff, the Varan "bailiff") Sieur Guion de Flor. Sieur Guion explained that he was looking to hire up some adventurers to discover what was happening to the farmer's livestock; apparently, vanishing. Whether or not the disappearance of a local boy from Battle Farm (Henshel, according to Ricki who made a name up for him on the spot) was related, the knight couldn't say.

So, agreeing to return to his manse with information in order to get 120 golden pillars (fulcre or ƒ as Varan orthography would have it -- Varan coinage is written in this manner: 120ƒ {gp, fulcre}, 120t {sp, turre}, 120s {cp, scutari}) the group set off. Antonio provided them with some much needed guidance about the local farms, but not before Sieur Guion left them his parting words: Farmer Balduin Bramble, tenant of Bramble Farm against the northern verge of the Vallain Wood, believed that the whole situation was caused by the ghost of a famous bandit.

The party went inside to drink and discuss their options. They asked little of the Black Keg's barkeep, Aldrus, save for a pitcher of his local beer. The four of them decided that they'd best ask Balduin Bramble some questions. This was done lickety split, so they finished up their cups of beer, swilled down what was left (or secretly poured it out into the rushes to splatter onto the floor) and hoofed it out of the town to the north.

Passing in the shadow of the grim ruin of the Florian keep hardly dampened their spirits, and before long they found themselves at the Bramble farm. A small cottage of unmortared river stone sheltered the old halfling with its wide porch and they joined him there, setting down in chairs nearby. He told tale after tale of the bandit Langrim the Blade, who had terrorized Casselflor back during the orc wars. He was convinced that the spirit of the bandit was stealing children to "replenish his own forces and ride again!" He told them they could play off Langrim's legendary vanity if they were to meet.

Cyosta (the party thief) meanwhile left to examine the fields and quickly found signs of passage on the freshly fallen snow. The party followed the trail into the woods and realized right quick it was leading to Glen Casse, the rumored bandits den of the orc wars. They spread out, leaving Antonio on the road with the party dogs (of which there are three: Caesar, Romeo, and Hephaestus) so they could slip quietly through the wood.

They discovered the hill-glade of Glen Casse and, seeing it empty, began to search it. A fire pit was at once evident, with the clear signs of chewed and gnawed bones amongst the ashes. As the entire party came to examine it, a blistering series of yaps and yips emerged from the hill, from behind a large rock. The party was under attack! They took cover behind nearby pine trees; both Antonio and Cyosta were struck by arrows before they could reach it.

Cyosta being the only party member with a ranged weapon, fired his bow up the hillside, loosing several arrows until he struck one of the kobolds that had appeared. The arrow took it through the eye and the other two immediately vanished behind the boulder. The party limped up after them to discover what they had feared: a warren of tunnels leading into the hill.

First the party argued about what to do for several minutes while the kobolds within organized. They debated smoking out the creatures, but were eventually afeard such actions would kill the boy (if he was truly in there). Cyosta determined to explore the rest of the hillside to see if there were other entrances. Before he could, however, Antonio healed him with a spell while Coi (the party fighter, Jocelyn) rushed into the sandy-floored cavern.

And straight into a trap, wherein four javelins were loosed at her. Batting them aside and bulling forward, she managed to reach the line of kobolds on the right while her dogs sank into the two on the left. They, of course, had emerged from tunnels that were out of sight from without, and a rapid heated battle ensued. On either side a kobold was killed while the other fled. This led to the most dreaded of situations: the split party.

I think I managed it fairly well, doing one round's worth of action with the left-hand group and one with the right. They split with Antonio and Coi together and Cyosta and Ovelaave (the elvish mage) on the other side, heading right-ways. The right-hand party blundered into a room of 9 kobold elite guards and 2 guard boars—which they had trouble distinguishing due to the low light leaving them only infravision to see by.

Ovelaave busted out his one spell (a judicious color spray) knocking out six kobolds, stunning the warthogs, and causing the rest of the creatures to flee. Murder ensued.

On the other side, Coi and Antonio unknowingly encountered and killed Skarax the Kobold King and his two guards before pressing on. The groups met together again in the breeding warren where they dispatched the remaining kobold females and young. Thus ended the first ever session of the virgin blades (they will probably hate that name).

Thursday, January 17, 2013

Avoiding Battle

It's been quite some time since I last had a substantial post -- almost a week, I believe. That's just too damn long. Unfortunately, work at the crucible of a tech start-up eats into your blogging time.

Today, we're going to talk about tools used to avoid battle, and again address some concerns of our friend Argo (you remember him). Not that he's had a negative response to the last issue (of thinking outside the rules), just that I have some further thoughts on the subject.

Some of this will be directly restating some things I recently read in a blog post about combat and D&D. I can't recall where I read it, but it was certainly linked from Zak's D&D with Pornstars blog. Anyhow, the blogger wrote that simply because earlier versions of D&D had very developed combat rules and very loose non-combat rules didn't mean the focus of the game was on combat. Indeed, it meant quite the opposite: that since combat was the final stage before being buried in a shallow grave (or more likely eaten by some unpleasant and gruesome creature) it was important that it be highly detailed in order to give players more control.

Playing later iterations of D&D, playing video games, and playing some of the later roleplaying games that have been released recently has convinced a whole host of people that the purpose of every roleplaying game is to fight. If it's not, the game will explicitly warn that about itself—Call of Cthulhu, for example—because the default situation is assumed to be simply this: Players will wander around and fight whatever they encounter. The fun of the game is in fighting and winning.

Well, I've never encountered an old school D&D game (here incorporating AD&D 2e in that umbrella term) that was run as a combat grinder. In all the games that I played, just as was stated in the nameless article that I can't recall, combat was a last resort. It was the final stage, a defeat in and of itself. The smart players found ways to avoid or stack combats so much in their favor that it was easy to win. There's a logic to this: you want to minimize risk. As PCs and as players, the goal was never to explore the variety of cool options you have to fight things, but rather to simply accomplish your ends without dying.

That's not to say those games weren't out there, being played. But those DMs couldn't have been too creative, if that was the drive of the game. There are as many ways to avoid combat as you can conceive literally, and for not one of them to ever work smacks of a railroad, the iron tracks of inevitability that are the anathema of the old school sandbox.

I have always modeled my combat in a way that parallels the early level experiences in Baldur's Gate: terrifying, prone to go bad very easily, and bone crunchingly awful. My players can attest that whenever they realize a combat is about to happen there is a sort of jittery feeling that passes around the virtual table. Will they survive this time?

For this reason alone, combat is something to be shunned, but beyond that it is also a poor way to deal with every problem. I suppose if, like Argo, you were only thinking of the tools of the game in terms of the rules for killing, you'd be inclined to resort to that every time. After all, if all you have are hammers, every screw starts to look like a nail. Or something.

I would encourage anyone who feels constrained in this way to break away from the combat-as-play chain. It severely hampers your ability to get things done, to get enjoyment out of the game, and to experience the setting in which you're playing—something, ostensibly, that you want to do considering you're playing a fantasy roleplaying game and not a miniature tactics game.

I've been thinking some today about how player goals and character goals synch up or fail to and what that means for the game, but the thoughts are still too fetal to be fleshed out on the mug, I think.

Today, we're going to talk about tools used to avoid battle, and again address some concerns of our friend Argo (you remember him). Not that he's had a negative response to the last issue (of thinking outside the rules), just that I have some further thoughts on the subject.

Some of this will be directly restating some things I recently read in a blog post about combat and D&D. I can't recall where I read it, but it was certainly linked from Zak's D&D with Pornstars blog. Anyhow, the blogger wrote that simply because earlier versions of D&D had very developed combat rules and very loose non-combat rules didn't mean the focus of the game was on combat. Indeed, it meant quite the opposite: that since combat was the final stage before being buried in a shallow grave (or more likely eaten by some unpleasant and gruesome creature) it was important that it be highly detailed in order to give players more control.

Playing later iterations of D&D, playing video games, and playing some of the later roleplaying games that have been released recently has convinced a whole host of people that the purpose of every roleplaying game is to fight. If it's not, the game will explicitly warn that about itself—Call of Cthulhu, for example—because the default situation is assumed to be simply this: Players will wander around and fight whatever they encounter. The fun of the game is in fighting and winning.

Well, I've never encountered an old school D&D game (here incorporating AD&D 2e in that umbrella term) that was run as a combat grinder. In all the games that I played, just as was stated in the nameless article that I can't recall, combat was a last resort. It was the final stage, a defeat in and of itself. The smart players found ways to avoid or stack combats so much in their favor that it was easy to win. There's a logic to this: you want to minimize risk. As PCs and as players, the goal was never to explore the variety of cool options you have to fight things, but rather to simply accomplish your ends without dying.

That's not to say those games weren't out there, being played. But those DMs couldn't have been too creative, if that was the drive of the game. There are as many ways to avoid combat as you can conceive literally, and for not one of them to ever work smacks of a railroad, the iron tracks of inevitability that are the anathema of the old school sandbox.

I have always modeled my combat in a way that parallels the early level experiences in Baldur's Gate: terrifying, prone to go bad very easily, and bone crunchingly awful. My players can attest that whenever they realize a combat is about to happen there is a sort of jittery feeling that passes around the virtual table. Will they survive this time?

For this reason alone, combat is something to be shunned, but beyond that it is also a poor way to deal with every problem. I suppose if, like Argo, you were only thinking of the tools of the game in terms of the rules for killing, you'd be inclined to resort to that every time. After all, if all you have are hammers, every screw starts to look like a nail. Or something.

I would encourage anyone who feels constrained in this way to break away from the combat-as-play chain. It severely hampers your ability to get things done, to get enjoyment out of the game, and to experience the setting in which you're playing—something, ostensibly, that you want to do considering you're playing a fantasy roleplaying game and not a miniature tactics game.

I've been thinking some today about how player goals and character goals synch up or fail to and what that means for the game, but the thoughts are still too fetal to be fleshed out on the mug, I think.

Monday, January 14, 2013

Busy busy busy

Not much time for blogwritin recently. For this I apologize.

Important news, however: Aaron Swartz, one of the heroes of the Open Access movement, creator of RSS and co-founder of Reddit, killed himself last week.

Read the Open Access Guerilla Manifesto at pastebin.

As a scholar and a vigorous opponent of the current system of IP laws, this hits home for me. Aaron fought ceaselessly for Open Access and a free information movement. Our heritage is knowledge; all people, not just the privileged few, should have access to our history, our past, our culture, our art, and all the thinking that has let us stand on the shoulders of giants.

Important news, however: Aaron Swartz, one of the heroes of the Open Access movement, creator of RSS and co-founder of Reddit, killed himself last week.

Read the Open Access Guerilla Manifesto at pastebin.

As a scholar and a vigorous opponent of the current system of IP laws, this hits home for me. Aaron fought ceaselessly for Open Access and a free information movement. Our heritage is knowledge; all people, not just the privileged few, should have access to our history, our past, our culture, our art, and all the thinking that has let us stand on the shoulders of giants.

Wednesday, January 9, 2013

Forewarned is Forearmed

After many lengthy discussions on why information-gathering is such an important skill (both with my players and here, on the Mug) I am happy to report that the Hounds of Aros did just that last night. While it took a long time and was not a coup by any means, they all feel more secure for the what they've learned.

To be succinct: Naur's master, Tholindinar, sits on the Council of the Silver Wizards. He is on the outs (for reasons they have yet to uncover) with his fellows, but he appears to be one of the more moderate members of the Silver Order, content to study magic and sneer at the Green Wizards (who are an active political player in support the Towerborn King) from afar.

The most powerful voice on the Council, a sorceress named Alodoriala, is his chief rival. She is openly antagonistic to the Green Wizards of the Tower, something that he sees as unnecessary and possibly dangerous. The catalyzing event is the discovery of an ancient elvish tome, The Book of Dreaming Secrets, replete with magic from the Fourth Age. Possession of this book would be a coup for either organization and it just so happens to have come into the hands of a wealthy merchantess in a nearby port town. Tholindinar hopes that his 'prentice and the Hounds can beat out an unpleasantly named adventuring company (the Scourge of Six) for the contract to go buy it and do so before the Green Wizard's own proxy company does the same. This will boost his standing in the Council, to be able to say it was his apprentice who retrieved the book.

Here's what the Hounds discovered last night:

Tholindinar is a double-edged sword; he may allow Naur to get into the Silver Manse, but mention of his name tends to be polarizing to the other Silver Wizards.

The Silver Wizards assume the contract is well in hand already and that the Council has decided on the Scourge.

Naur has planted the seems of his own companies' hiring in the mind of the Undermaster Velhandar and also hinted that he might abandon Tholindinar if properly enticed.

Oloz learned of the adventuring parties that reside in Tyrma, the most famous of which are the Blades. They are a group of houseless knights and a wind priestess, and they generally serve the Tower. He also heard brief mention of the Woodwatchers and High Harps, but the poet he spoke with was more dismissive of them.

Further, he learned that the Scourge of Six hails from Arvoriena and is extremely mercenary. They are led by a wizard named Salainen. Amongst their number is a Murathan swordsman called Al-Saif and an elvish thief named Findal. Predictably, they aren't known for their kindness but rather for following the coin wherever it may lead.

Through listening to idle bar-talk between two ship's masters in the White Swan, they learned the houses generally perceived to support the Alcosa. Rumors centering around a civil war seem to be common, for the Alcosa fear that if the Towerborn King is allowed to have his way when he dies the Green Wizards will convene an Electoral Council which has not been done in centuries upon centuries.

To be succinct: Naur's master, Tholindinar, sits on the Council of the Silver Wizards. He is on the outs (for reasons they have yet to uncover) with his fellows, but he appears to be one of the more moderate members of the Silver Order, content to study magic and sneer at the Green Wizards (who are an active political player in support the Towerborn King) from afar.

The most powerful voice on the Council, a sorceress named Alodoriala, is his chief rival. She is openly antagonistic to the Green Wizards of the Tower, something that he sees as unnecessary and possibly dangerous. The catalyzing event is the discovery of an ancient elvish tome, The Book of Dreaming Secrets, replete with magic from the Fourth Age. Possession of this book would be a coup for either organization and it just so happens to have come into the hands of a wealthy merchantess in a nearby port town. Tholindinar hopes that his 'prentice and the Hounds can beat out an unpleasantly named adventuring company (the Scourge of Six) for the contract to go buy it and do so before the Green Wizard's own proxy company does the same. This will boost his standing in the Council, to be able to say it was his apprentice who retrieved the book.

Here's what the Hounds discovered last night:

Tholindinar is a double-edged sword; he may allow Naur to get into the Silver Manse, but mention of his name tends to be polarizing to the other Silver Wizards.

The Silver Wizards assume the contract is well in hand already and that the Council has decided on the Scourge.

Naur has planted the seems of his own companies' hiring in the mind of the Undermaster Velhandar and also hinted that he might abandon Tholindinar if properly enticed.

Oloz learned of the adventuring parties that reside in Tyrma, the most famous of which are the Blades. They are a group of houseless knights and a wind priestess, and they generally serve the Tower. He also heard brief mention of the Woodwatchers and High Harps, but the poet he spoke with was more dismissive of them.

Further, he learned that the Scourge of Six hails from Arvoriena and is extremely mercenary. They are led by a wizard named Salainen. Amongst their number is a Murathan swordsman called Al-Saif and an elvish thief named Findal. Predictably, they aren't known for their kindness but rather for following the coin wherever it may lead.

Through listening to idle bar-talk between two ship's masters in the White Swan, they learned the houses generally perceived to support the Alcosa. Rumors centering around a civil war seem to be common, for the Alcosa fear that if the Towerborn King is allowed to have his way when he dies the Green Wizards will convene an Electoral Council which has not been done in centuries upon centuries.

Tuesday, January 8, 2013

Just Who Can Use Magic, Again?

I've always been an equal-opportunist when it comes to magic. Something that's stuck with me from 7th Sea is the notion that in a world where people are born with the ability to use magical powers the formation of a permanent aristocracy is not only borne out by the abilities of that aristocracy but actually justified. In a sense, magic users are truly better than other people.

Now of course, this doesn't hold if the skill is one that ignores the barriers of class or race. It would almost be a requirement for the ability to do magic to pass along hereditary lines for such a stratified nobility to form. For whatever reason I balked at the idea, and have strongly been in favor of a magic that was knowable by anyone who dedicated enough time and energy to studying it (and who possessed at least an average amount of human intelligence, of course). Still, there are races in the 10th Age that not only do not possesses a culture of magic but have no magical aptitude at all (dwarves and halflings come to mind).

But what about a world where magic is an ability that takes shape in a random, unidentifiable pattern amongst the population? This still singles out some people as "exceptional," which is something that I reject on a gut level. I'm not certain why—perhaps because of my ingrained belief that "exceptional" people are simply those with the drive to improve, that no matter the baseline of skill any given person starts with, it is dwarfed in importance by the effort put into developing that skill.

I can't think of anyone I know that's ever run a game where the option presented itself who has chosen to enforce magic as a special marker, something that makes you apart from the rest of the population. And yet, one of my favorite fantasy series (R. Scott Bakker's Second Apocalypse) features magi who are granted power in exactly this manner. They simply exhibit the skill when they are young and then are either snatched up by the powerful Schools.

I'd love to hear from you guys about your preferences. What kind of magics do you allow (if you run a game with magic, of course) and what kind do you prefer? Is there something inherently alluring about the prospect of being given (by random lot) the ability to control the very fabric of the universe? It seems to be a common trope in fantasy books that sorcery is an inborn power... so where do you stand?

Now of course, this doesn't hold if the skill is one that ignores the barriers of class or race. It would almost be a requirement for the ability to do magic to pass along hereditary lines for such a stratified nobility to form. For whatever reason I balked at the idea, and have strongly been in favor of a magic that was knowable by anyone who dedicated enough time and energy to studying it (and who possessed at least an average amount of human intelligence, of course). Still, there are races in the 10th Age that not only do not possesses a culture of magic but have no magical aptitude at all (dwarves and halflings come to mind).

But what about a world where magic is an ability that takes shape in a random, unidentifiable pattern amongst the population? This still singles out some people as "exceptional," which is something that I reject on a gut level. I'm not certain why—perhaps because of my ingrained belief that "exceptional" people are simply those with the drive to improve, that no matter the baseline of skill any given person starts with, it is dwarfed in importance by the effort put into developing that skill.

I can't think of anyone I know that's ever run a game where the option presented itself who has chosen to enforce magic as a special marker, something that makes you apart from the rest of the population. And yet, one of my favorite fantasy series (R. Scott Bakker's Second Apocalypse) features magi who are granted power in exactly this manner. They simply exhibit the skill when they are young and then are either snatched up by the powerful Schools.

I'd love to hear from you guys about your preferences. What kind of magics do you allow (if you run a game with magic, of course) and what kind do you prefer? Is there something inherently alluring about the prospect of being given (by random lot) the ability to control the very fabric of the universe? It seems to be a common trope in fantasy books that sorcery is an inborn power... so where do you stand?

Monday, January 7, 2013

Problem of Language

As an avid Tolkienite I've suffered through an issue which bats me back and forth each time I consider it, and that issue is: Names and language, specifically place-names. I've striven on occasion to turn English region-names into their Varan equivalent on all my maps. Seareach became Mermarche, Goldhook Auruxol, etc. But what if it makes more sense to leave them as translated names? Should Casselflor be left as it is, or should the town be known as the Castle of Flowers? Should the Portam Regis be forever known that way, or is it really the Gate of Kings?

Tolkien would have us leave it in the native tongue of the world, but he was also a philologist and linguist. George R. R. Martin would translate it (Maidenpool, Bitterbridge, King's Landing, Casterly Rock, The Eyrie, etc.) though there is clearly some alternate linguistic scheme at work in Westeros. Which way is right? Is Giant's Arch or Gigantarch a better name? Should Couer County truly be known as County Heart? I cannot seem to land on a decision one way or the other.

Tolkien would have us leave it in the native tongue of the world, but he was also a philologist and linguist. George R. R. Martin would translate it (Maidenpool, Bitterbridge, King's Landing, Casterly Rock, The Eyrie, etc.) though there is clearly some alternate linguistic scheme at work in Westeros. Which way is right? Is Giant's Arch or Gigantarch a better name? Should Couer County truly be known as County Heart? I cannot seem to land on a decision one way or the other.

Thursday, January 3, 2013

You Can Survive Some Awful Stuff Done to Your Body

When I was younger I felt that a lot of roleplaying games underestimated the lethality of weapons. From swords to guns, you should pretty much be dead after you're struck, thought I.

It was only as I got older that I realized the opposite was true. Certainly, if your head was cleft from your shoulders or your brainpain annihilated you would be dead. However, as I became more and more knowledgeable about history I began to see the cases in which grievous bodily harm didn't result in death.

Henry V was shot in the face with an arrow and survived. There have been many carabinieri and condotta that were shot with lead balls and survived to tell the story. In one of the classes I took in medieval studies (Rome and the Barbarians, with Prof. Robin Fleming) we looked over a lot of human remains... remains that displayed healed sword-cuts, broken bones that had been set and other such wounds that failed to slay their target.

So as I looked over HP and waded once again into the complex HP debate I realized that I actually liked HP even more than I thought. It's flexible, represents real and lasting harm done to the character (meaning a blow, even if it lands, that does little more than bruise is probably not HP damage) and also accurately depicts the moment of a debilitating strike: ie, most warriors don't get worn down in combat, grow sword-weary and sluggish, and then fall; rather, it is more likely that they will sustain minor injury until at last their guard is down and the stroke which drops them is delivered.

It was only as I got older that I realized the opposite was true. Certainly, if your head was cleft from your shoulders or your brainpain annihilated you would be dead. However, as I became more and more knowledgeable about history I began to see the cases in which grievous bodily harm didn't result in death.

Henry V was shot in the face with an arrow and survived. There have been many carabinieri and condotta that were shot with lead balls and survived to tell the story. In one of the classes I took in medieval studies (Rome and the Barbarians, with Prof. Robin Fleming) we looked over a lot of human remains... remains that displayed healed sword-cuts, broken bones that had been set and other such wounds that failed to slay their target.

So as I looked over HP and waded once again into the complex HP debate I realized that I actually liked HP even more than I thought. It's flexible, represents real and lasting harm done to the character (meaning a blow, even if it lands, that does little more than bruise is probably not HP damage) and also accurately depicts the moment of a debilitating strike: ie, most warriors don't get worn down in combat, grow sword-weary and sluggish, and then fall; rather, it is more likely that they will sustain minor injury until at last their guard is down and the stroke which drops them is delivered.

Wednesday, January 2, 2013

The Small Things

Flavor, as in the flavor of lore, doesn't seem to be present in sweeping histories. Those are backdrop that help explain the world and where everything is. But those don't carry flavor of their own. It's hardly helpful to get a feel of the world if you know that the Thegnari marauders entered Llyris in such-and-such-a-year and the Llyrians incorporated Thegnari horseculture into their ideals of knighthood at such-and-such-a-date, even less so that such-and-such-a-king died in such-and-such-a-manner on such-and-such.

That stuff is all important. That's NOT flavor. Flavor comes from the small things.

Here's an old list of some small things that I made to help give regions flavor:

That stuff is all important. That's NOT flavor. Flavor comes from the small things.

Here's an old list of some small things that I made to help give regions flavor:

Atva-Arunë

The Skinchanger Kingdoms

Hardroot, a small brush that grows near large trees, Hardroot is said to have restorative properties.

Skins and Furs (primary trade)

Tin and Iron (lots of iron)

Jet

Amber

Oddities: Skinchangers exist in much greater numbers amongst the Northmen than they do in the heartland. Northmen sometimes wield great two-handed swords, the use of which are rarely seen by heartland warriors.

The Inner Sea

Olive oil

Glintwine, a general term for mulled hot wine

Arunë-Oriens

Moon Kingdoms

Silk (from Diaojiong)

Spices; pepper (minor) and cinnamon (large amounts), clove

Tin (huge trade!)

Garnet, onyx

White gold

Oddities: Goblin-priests of both sexes often wear jewelry that are traditionally “female” in Atva-Arunë: earrings, necklaces. They also perfume themselves extensively (not with alcohol based perfumes, as these do not exist in the 10th Age; rather, with pomanders and other strong-scented caches of herbs, spices, or incense as well as thick salves and essential oils suspended in fat). Indeed, all Moon Goblins are fond of perfume and incense.

Hadash

Sweetwater (a rose-flavored liquor favored by Rayans)

Dragon’s Tongue, a virulent weed that possess toxic properties

Hearthblossom, a flower that only opens at night and glows orange like a fire

Magestone, a purple-black semi-transparent stone said to be more valuable for working magic than even emeralds.

Oddities: The men of Hadash are said to be partially descended from elves, colonies having been established there during the early seafaring period of the elvish kingdoms. They have an intense love for silver, and mint no gold coins, valuing silver much more highly. They are a dark-skinned folk with sharp clever features, so it may be that the rumors are true. Myth speaks of elvish communities hidden in the high desert.

Ishtria

Shadowbloom, thought to be a kindred plant to the Hearthblossom, the Shadowbloom is a purple flower that only blooms during the day. Scholars say that it is perceptibly cooler near a patch of shadowbloom.

Seagrass, cultivated by the few dwarven colonies in Ishtria, Seagrass makes for a disgusting cocktail when fermented; however, it is better than the salt-water near the dwarven port halls. Seagrass Wine is particularly reviled in the north.

Glass, Ishtria and Khewed alone maintain a widespread glass production trade. Thus, almost all glass in use by men comes from Ishtria or Khewed via Ninfa. The same cannot be said of dwarves and elves, who have their own glass manufactories.

Cloves

Desert Sapphires, are a very valuable form of amber that are prized by all races of the north and seem to be found only in desert climes.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)